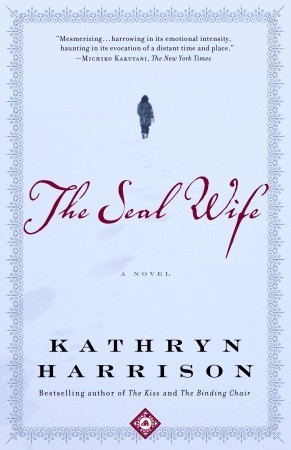

Kathryn Harrison’s most recent novel is a finely detailed if somewhat dull historical fiction that considers the development of one man’s character in the context of developing scientific technology.

In 1915 the newly founded Weather Bureau sends young meteorologist Bigelow to set up an observation station in the frontier town of Anchorage, Alaska. Too sensitive and intellectual to fit in with the rowdy locals, Bigelow is consumed by two activities only: monitoring the weather, and pursuing a relationship with the silent, nameless Aleut woman who “he finds not merely beautiful but necessary.” Devastated when she disappears suddenly without explanation, he throws himself into his work, single-handedly designing and constructing an enormous kite to take temperature readings hundreds of feet in the air. This invention sparks a great deal of interest in Anchorage and establishes Bigelow as a talented, if isolated, innovator in the new science of meteorology. Despite this success, his obsession with his unnamed lover gives him no rest. He attempts to find release from his fixation in the arms of a series of women.

Contrasted starkly against each other, the novel’s female characters are almost mythic archetypes rather than real people. This is not the only instance in which the author’s intimations of the mythic and magical fit uncomfortably within the novel’s historical context. Harrison’s greatest strength is evoking turn-of-the-century Alaska. The details she includes, along with her use of the present tense, make the author’s World War I era Anchorage immediate. Descriptions of the town’s bathhouses and brothels as well as frank scenes depicting Bigelow’s sexual relations divest the past of its mask of propriety and make it accessible to contemporary readers. Set against this backdrop of well-researched fact and well-supported conjecture, however, are the novel’s feeble gestures toward mysterious enchantment. Its title and its scattered references to seals imply a connection between Bigelow’s lover and the seal creatures of Celtic legend that may explain the Aleut’s mystical silence. But Harrison does not pursue that association closely enough to make it interesting. The thin clues that remain serve only to taint the historical framework she has constructed carefully, leaving The Seal Wife in limbo somewhere between an incredibly detailed historical fiction and a beautiful, otherworldly legend.

The uncomfortable juxtaposition of historical accuracy and the unexplained is not the only place where The Seal Wife falters, however. At its center, the novel tells the story of a vulnerable young man trying to understand the relationship between emotional need and erotic desire. This thematic focus almost justifies the many sex scenes in The Seal Wife that might otherwise be considered gratuitous. In the end, however, no matter how often or how graphically Harrison describes Bigelow’s desire for the Aleut, it remains as inexplicable as his fascination with meteorology. Unfortunately, even Harrison’s gripping, provocative prose cannot make the weather as interesting for readers as it is for Bigelow. Neither can it conquer the Aleut’s silence to reveal the allure that makes her the central motivation of the entire novel.