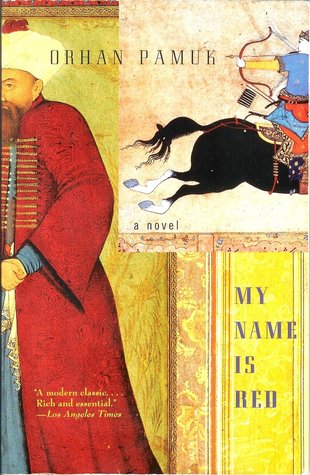

While the name Orhan Pamuk may not currently arouse great interest in American literary circles, his Turkish compatriots recognize him as one of their nation’s most important thinkers. His work sells like nothing else in Turkey, and his controversial novel The Black Book (1990, English translation 1995) garnered international recognition for its unique style and engulfing plot. The latest offering from this respected artist is an English translation (2001) of his 1998 book My Name is Red. A novel unlike any written in English, it should impress and reward every thoughtful reader.

Pamuk’s genius lies in his talent for philosophic thought, and ability to depict a culture of customs and ideas utterly foreign to the Western imagination. With Pamuk’s words as a guide, even the defunct and unusually foreign realm of Ottoman court painters in the late sixteenth- century becomes vivid and intellectually poignant.

The novel opens to the disembodied voice of the murdered court miniaturist Elegant Effendi, one of a group of artists that decorated illuminated manuscripts for their Sultan, as he laments his fate and demands retribution upon his treacherous killer. Quickly, this crime reveals an elaborate and troubling conflict surrounding a secret manuscript whose possible heretical content has caused friction among the various miniaturists working on it. This infighting culminates in Elegant’s murder. Disturbingly, the culprit who stole Elegant’s life appears to be one of his fellow miniaturists still working secretly on the clandestine document.

Instead of venturing down the heavily beaten path of murder mystery, however, Pamuk continues a measured and creative journey deeper into various lives within the Ottoman Empire. Additional characters emerge and their lives and worries enliven the story and introduce a host of new considerations for the novel. There is the unorthodox love story between the gorgeous Shekure and her cousin, the wandering Black. There is the message-passing Jewish fabric seller, Esther, who continually arranges marriages between others. There is Master Ossman, the head of the Sultan’s miniaturist workshop, with his contemplations about the painfully temporal existence of an artist constantly striving for immortality through his work. There is the nameless storyteller in the illegal coffee shop whose tales of personified pictures are alternately lewd and frighteningly incisive. There is even the self-torturing murderer of Elegant Effendi, to whose painful inner dialogue the reader is periodically privy.

Among this large and various cast of characters and issues, communication is a complex art. For instance, there is no omniscient third-person narrator. Instead, each chapter has its own personal narrator. And thus the story is assembled through the thoughts and impressions of the characters, in the same manner as William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying (fortunately, Pamuk’s supple prose, like Faulkner’s, is well suited to the task of depicting a host of different characters). In addition, the book is never clear on the conflict surrounding the Sultan’s secret book. The friction that the infamous manuscript causes is real enough to result in multiple murders, but its true religious threat is never actually confirmed. These expressions of the nebulous nature of human society are ingenious and probably the greatest strength of the novel; Pamuk never forces some direct and simple truth upon the reader but leaves the complexity of reality very much alive within his imagined realm.

Even communication between characters is obscured by various means. The lovers Black and Shekure, who first meet face-to-face only after more than 150 pages, communicate in half-sincere notes passed along by a strange Jewish fabric vendor named Esther. The language of the lovers expresses well the wonderful lack of communication between them:

On my second visit after twelve years, she didn’t show herself. She did succeed, however, in so magically endowing me with her presence that I was certain of being, somehow, continually under her watch…Knowing this, I also imagined I was continually able to see her. Thus was I better able to understand Ibn Arabi’s notion that love is the ability to make the invisible visible and the desire always to feel the invisible in one’s midst.

But the lovers are not the only characters with communication difficulties. The miniaturists also experience a sort of inability to communicate with one another, but here the impeding factors are things like pride and jealousy. And perhaps the character who experiences the greatest trouble expressing himself is the lunatic who took Elegant’s life. As he secretly tails Black one night, he laments beautifully about his strangely helpless situation:

We were two men in love with the same woman; he was in front of me and completely unaware of my presence…we traveled like brethren through deserted streets given over to battling packs of stray dogs, passed burnt ruins where jinns loitered, …just out of sight of brigands strangling their victims, passed endless shops, … and stone walls; and as we made ground, I felt that I wasn’t following him at all, but rather, that I was imitating him.

The magic of this novel does not only reside in what it refrains from doing, but also in something that it accomplishes with flourish. After the plot evolves into a sleuth-like search for the homicidal miniaturist, an elaborate discussion of the philosophy of miniaturist art from the late sixteenth century pervades the book’s subsequent discussions. Somehow, even a topic as potentially soporific as the theory of Islamic miniaturist art supplies wonderful fodder for an engaging, intellectual novel. Among other benefits, this intense debate concerning theories of art (primarily the Venetian style and the miniaturist style) provides tidbits such as:

“[T]hey [the Venetians] also want us to know that simply existing in this world is a special, very mysterious event. They’re attempting to terrify us with their unique faces, eyes, bearing and with their clothing whose every fold is defined by shadow. They’re attempting to terrify us by being creatures of mystery.”

What Orhan Pamuk has created in his latest novel is a wholly unique literary encounter. The story is intriguing and well told; the prose is, at times, greatly affecting; and the artistic execution must be admired. And although the style of the writing makes for a challenging read, the effort expended by the reader will be repaid. Perhaps soon Pamuk, no longer a “creature of mystery” to the western world, will find his deserving place on the shelves of American readers.