Review provided by Soccer ABC.

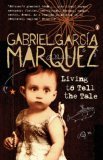

Over lunch with his father, a twenty something Gabriel García Márquez was discussing the difficulty many writers have in writing their memoirs when they can no longer remember the events of their life. When his six-year-old brother came into the kitchen and heard this remark he replied matter-of-factly, “Well, then the first thing a writer ought to write is his memoirs, when he can still remember everything.” One could say that García Márquez has done exactly that, creating fiction that is so intimately connected to his life that the two are inseparable. Very few writers can boast of such a complete and defined symbiosis of experience and imagination in their work. Living to Tell the Tale, the first of his projected three-volume autobiography, treads alongside the beguiling and powerful narratives he has been writing for over half a century.

This aptly titled book spans from his birth in 1927 through the start of his career as a writer, ending in cliff-hanger form when, in the 1950s, he departs for Europe and proposes to his childhood love. It has the feel of a conversation over coffee, a spontaneous and uninterrupted flow in the author’s memories of people, places, and events. He includes stories of his unique family members, his consuming career in journalism, the myths and mysteries of his beloved Colombia, and, above all, his fervent desire to become a writer. The memoir is marked by its refusal to adhere to an authoritative record or a structured chronology of the author’s life. Set against the political, social, and literary events in Colombia and the greater Caribbean landscape from the 1920’s through the 1950’s, the central stories of García Márquez’s life exist in full form.

The book is framed around a trip he took in his early twenties with his mother to sell his grandparents’ house in the tiny Colombian town of Aracataca. In the midst of this account he suddenly pulls back into his childhood and recalls his earliest memories of that very house and his extraordinary family. By the end, he effortlessly returns to the pivotal moment on the trip when he declares to himself and his family: “I’m going to be a writer . . . Nothing but a writer.”

The book in its original Spanish is written with a beauty that cannot be matched in any other language, but for those who possess an imperfect knowledge of the Spanish language, Edith Grossman’s English translation is equally eloquent and evocative. The prolific Grossman is also responsible for the most lavishly praised of three new versions of Don Quixote. To date she has translated more than 30 books of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry by Spanish-language authors, many of whom are members of the great Latin American literary “boom” of the ’60s and ’70s. She is especially familiar with García Márquez’ literary voice, having already translated Love in the Time of Cholera, The General in his Labyrinth, Strange Pilgrims, Love and Other Demons and the non-fiction News of a Kidnapping before taking on Living to Tell the Tale. García Márquez has given her the ultimate seal of his approval, telling her, “You are my voice in English.” The language of Edith Grossman’s translation frequently skirts the boundaries of poetry and mirrors the circling prose which defines Márquez’s style without sacrificing the lyrical quality which make his phrasing so striking and haunting.

Much of the account focuses on the influence of his childhood interactions with his family, especially his parents and maternal grandparents. He states early on: “I cannot imagine a family environment more favorable to my vocation than that lunatic house, in particular because of the numerous women who reared me.” The sometimes all-consuming family environment was a powerful source of inspiration “because of the creative fever with which we lived in our house, where the most unusual things always seemed possible.” He charts the development of his trademark magical realism through the fantastic yet matter-of-fact stories of the women of the house in their dealings with ghosts, miracles, and a bird with iridescent feathers that flies out of a bed at the moment of an exorcism. The family’s involvement in the fantastic spurred his writing: “My stories were simple episodes from daily life that I made more attractive with fantastic details so that the adults would notice me . . . these were a budding narrator’s rudimentary techniques to make reality more entertaining and comprehensible.”

The narrative shifts to a coming-of-age story as the author recounts his formative years in secondary school and college. Along with the details of the usual dorm mischief and schoolboy battles of honor in boarding school, García Márquez launches into discussions of the literary pantheon he devoured while growing up. In the primary school library, he eagerly read adolescent classics like Treasure Island and The Count of Monte Cristo. “I devoured them letter by letter, longing to know what happened in the next line and at the same time longing not to know in order not to break the spell. With them, as with The Thousand and One Nights, I learned and never forgot that we should read only those books that force us to reread them.” Upon entering high school he moved to the post-World War II translations of Borges, Steinbeck, Hemingway, Dos Passos and Faulkner. García Márquez and his friends proved to have an unbounded enthusiasm for literature of all kinds, reading Quevedo, Arthur Conan Doyle, and James Joyce with equal pleasure. He even cites specific works which affected his development as a writer, such as Joyce’s Ulysses which “provided invaluable technical help to me in freeing language and in handling time and structures in my books.” From Kafka and the character Scheherazade, he learned that “it was not necessary to demonstrate facts: it was enough for the author to have written something for it to be true, with no proof other than the power of his talent and the authority of his voice.”

He continues on his developmental journey to describe his later exploits as a professional journalist writing for a variety of newspapers. Ranging from editorials to soccer commentary, his writing jobs, with various limitations of time and space, provided valuable lessons in craft. He reflects that the experience of having to write the daily column “La Jirafa” “had fulfilled its mission of imposing on me a daily job of carpentry so I could learn how to write, starting from zero, with tenacity and the fierce aspiration to be a distinctive writer.” Even the presence of censorship was useful as it forced him to find inventive ways to report the truth. During La Violencia, a ten-year period of violence and civil war, all articles submitted for publication had to be approved by government censors. Working during this period, García Márquez came to view journalism as a “literary genre” rather than a profession. To him, “the novel and journalism are children of the same mother,” as fact and fiction blended together even in the reporter’s work. An editor once advised García Márquez that “credibility depends a good deal on the face that you put on when you tell the story,” which remains true today.

Colombia’s violent history is always in the background, as García Márquez recalls such historical episodes as the Bananeras massacre, a banana labor strike in 1928 that escalated into the massive slaughter of United Fruit Company workers, and the Bogotazo, a 1948 uprising by the Liberal party that resulted in massive destruction and looting in the country’s capital. These historical accounts do much justice to García Márquez’s experience as both a novelist and a journalist. While his prose is in his imaginative signature style, the historical content is as rigorously researched as any of his extensive journalistic works.

For those who have been transfixed by García Márquez’ fiction, Living to Tell the Tale holds a special treat. Real-life influences of his novels are revealed, though it takes an intimate knowledge of his work to catch them all. The star-crossed, tenacious lovers of Love in the Time of Cholera turn out to have been based on the maligned courtship of García Márquez’ parents. He admits that “they were both excellent storytellers and had a joyful recollection of their love, but they became so impassioned in their accounts that when I was past fifty and had decided at last to use their story in Love in the Time of Cholera, I could not distinguish between life and poetry.” His grandfather, waiting in vain for a soldier’s pension that never arrives, assumes the form of the protagonist in “The Colonel to Whom Nobody Writes.” The partial unraveling of One Hundred Years of Solitude is especially fascinating. Macondo was forged directly from his impressions of Aracataca, and its name emerged from the landscape of the train ride home, which moved inexorably toward “the only banana plantation that had its name written over the gate: Macondo.” He writes that “with the first step I took onto the burning sands of the town,” Aracataca instantly became Macondo, “an earthly paradise of desolation and nostalgia,” and his one great subject became his family, “which was never the protagonist of anything, but only a witness to and victim of everything.” The same real-life influences are also found in novels like Leaf Storm and Chronicle of a Death Foretold, which, as a promise to his mother, García Márquez did not to publish until the death of the mother of the actual murdered man. Despite these specific unveillings, a hallucinatory spectacle remains in García Márquez’s fiction. With these dream-like confidences, the reader is left wondering what is real and what is in the realm of imagination.

The end of the book finds García Márquez on the brink of great adventures in love and a departure for Europe. Marriage, children, and the great novels of the future await. Yet, with this first quarter century of the author’s life, it is possible to track the sparkling narrative voice which will continue to dazzle readers in the forthcoming volumes. Living to Tell the Tale is in no way a conventional literary memoir but is rather, as the critic Christopher Carduff writes, “a way for an elderly master to revisit the monuments of his life’s work and to view them from a different angle, to exhibit them in a different light, and to at once elucidate them and deepen their mystery.” The depth and richness of this book transcends straightforward autobiography by drawing upon the artistry and tremendous narrative skill of the author’s best fiction. His epigraph provides the best description of what it is to write fiction and to write the story of one’s life: “Life is not what one lived, but what one remembers and how one remembers it in order to recount it.”