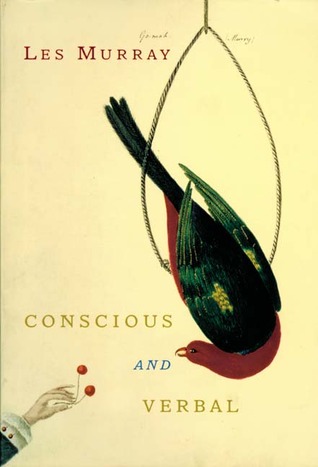

Conscious and Verbal: Poems 1996-2000 signals a change in the verses of poet Les Murray. While traces of the man known for his rugged, political poems can still be found, his new work is quieter, more pensive and sometimes tender. This change in attitude resonates with Murray’s survival, in 1996, of a three-week-long coma. These poems retain and reflect the silent wonder of an intensive care ward, while the phrase “conscious and verbal” is taken from a newspaper article, which used the words to describe Murray during his recovery.

Murray began his career writing poems about the experience of the poor, the rural, and the marginalized of contemporary Australia. His first book of poems, The Ilex Tree, was published in 1965, and he has remained relatively prolific ever since, winning international acclaim by the early 1990s and becoming Australia’s most famous poet. Conscious and Verbal offers a more finely grained world in which our presence is only contingent and in which we must discover our own place.

Born in New South Wales, Australia in 1938, Murray spent his childhood and adolescence working on a dairy farm. Early in life, he developed an acute eye for injustice and an impatience for the verbose, flowery language often employed to mask it. Murray began to write in his own style, a style that is as thematically and linguistically irreverent as it is formally flawless. For Murray, a poem is an exercise in balance between the impolite and the impeccably trained, a tension that has long characterized his work.

Conscious and Verbal shows a new attention to the process of poetic creation, mirrored in his description of construction in rural Australia in “The Water Plough”:

…Building with the country,

not on it. Building and reshaping it,

cuttings and bywashes and ramps,

finding the walls it would agree to,

stopping the chainsaws of erosion-water,

arresting them to spoons of sky light…

Like the anonymous builders of “The Water Plough,” Murray knows how to make his pieces work not in spite of their quotidian language, but because of it. He painstakingly creates his poems out of the everyday materials of speech, remnants left behind or overlooked by other poets. While Murray has always used prosaic words, one surprise in this new volume is that they are applied differently now, in more obtuse metaphors.

In Conscious and Verbal, Murray’s language not only indicates the often-neglected aspects of our daily life; it also celebrates the ambiguities that flourish in these gaps in our attention. Whereas before Murray’s comparisons were more often made with a nod to the dynamic, tangible life of the poet, as if to keep the poem anchored in the physical present, Murray now seems more concerned with linking his poems to something far more indistinct and perhaps sublime.

In a poem called “Sound Bites,” Murray explores a verbal space that is not constructed out of linear progressions of meaning, but is suggested by language’s ambiguity and implication. The poem gestures toward something greater in which all of that consciousness is contained. Murray writes, “it’s a body-prayer, a shower: you’re/ in touch all over, renewing, enfolded in a wing—“ and later, “but I bask in the pink that you’re in (Repeat).” “Sound Bites” relates to the reader in an entirely new manner than Murray’s past poems, forcing the readers to accept kinship with something that is perhaps subconscious and accessible to them only outside of individual, conscious experience.

Still, the physical world remains important to Murray in Conscious and Verbal. It is a literal landscape to be inhabited and appropriated, not distantly praised or clinically assessed. Whether he dives into a pond of “eel jelly…thick as beef, smelling aluminum,” in “The Water Plough,” or watches people begin to “breathe watercolors” of light in “The Mowed Hollow,” Murray’s relationship to the elements is dynamic. Indeed, what is most affecting in Murray’s poems is his success at denying what other poets have so long embraced as their raison d’être: the poet’s own alienation from the world.

This engaged, exuberant life in his poems has long been one of Murray’s characteristic strengths; we get the sense that he not so much writes these scenes as transcribes them from a tangible and complete sensory experience of his own. Whereas other poets observe and then translate their experience into poetically appropriate language, Murray abandons propriety with his startling immediacy. His poems stay closer to his initial impulses and inspirations. His language expresses exactly what the world is, not what it is like, for similes involve a certain degree of separation from the actual experience.

Murray’s use of the prosaic, then, is fundamental to his poetic purpose. He is a poet-rebel against the convolutions of verbiage that hold the reader apart from the experience of the poem. Like the arctic bear of “The Ice Indigene,” Murray “can be simple anywhere he is going.” He has discovered, again and again, the power of recognition and the engagement it creates in poems, so often alienated from, and alienating to, the reader. In the final part of “You Find You Can Leave It All Behind,” a poem more explicitly about his time in a coma than the others, Murray enters our minds:

God, at the end of prose,

somehow be our poem—

When forebrainy consciousness goes

wordless selves it’d barely met,

inertias if rhythm, the life habit

continue to battle for you.

Murray’s poems of renaissance in Conscious and Verbal (as in the rest of his oeuvre) assure us that wonder abides everywhere, that the space poems inhabit is not only in the leather-bound kingdom of Beinecke, but also in the unmapped regions of our most mundane moments. Murray offers us the possibility that poetry is as miraculous and varied as beauty itself, a beauty he is able to find in the most unexpected places. Indeed, perhaps the greatest beauty revealed by his work is the potential for new understanding of our unexamined experience, the unconscious, and its miraculous vastness of possibility.