Anthony Doerr likes to list. It’s a style that becomes quickly apparent in the first few stories of The Shell Collector and then continues throughout his collection. Sometimes the lists are funny: “Tequila, reminders of the Marshall Plan, rudely phrased questions about the queen’s gender and the president’s bedside fancies” are the “standard provocations” that set two groups of British and American anglers off on a six month, six continent, no-expenses-spared fishing contest in “July Fourth.” Other times, the lists are stunningly beautiful, as when the hunter in “The Hunter’s Wife” looks out the window on his first planeride to see “rose-lit cumulus, houses and barns like specks deep in the snowed-in valleys, all the scrolling country below looking December—brown and black hills streaked with snow, flashes of iced-over lakes, the long braids of a river gleaming at the bottom of a canyon.”

And at other times Doerr’s lists are frightening. “Decapitated children, drugged boys tearing open a pregnant girl, a man hung over a balcony with his severed hands in his mouth” as well as “rape, murder, an infant kicked against a wall, a boy with a clutch of dried ears suspended from his neck” are all images of the Liberian civil war seen by the protagonist of “The Caretaker.” Listing allows Doerr to convey a large amount of information in a small space or to describe years in a few instants. It is the device on which many of these stories hinge: an economy of words used to portray the passing of time. Doerr can describe intervening years in a sentence or two and then move ahead to focus on a particularly important moment in paragraphs of vivid detail.

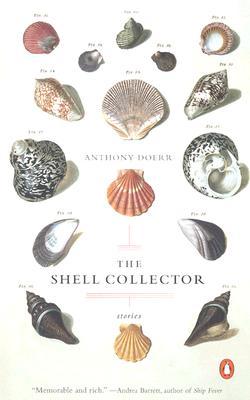

These stories are certainly about the important moments and days that make up a person’s life, but they can also encompass decades, as most of the stories in this collection do. The title story chronicles the life of a blind Canadian man who has become a collector of shells on the coast of Kenya in his sixties. The narrator takes two paragraphs to describe the years between the moment he first touched a shell and his arrival in Lamu. Once again, a list compactly describes his life: “He returned to Florida, earned a bachelor’s in biology, a Ph.D. in malacology. He circled the equator; got terribly lost in the streets of Fiji; got robbed in Guam and again in the Seychelles; discovered new species of bivalves, a new family of tusk shells, a new Nassarius, a new Fragum.” The story is not about those years, though; instead, it focuses on the period after which the shell collector finds a poisonous cone shell that seems capable of curing life-threatening diseases. Even in the alternative reality of such a situation, the collector’s academic accomplishments seem far-fetched, and Doerr’s sliding perspective gives too much visual information to make the man’s blindness believable anyway. Fortunately, these small weaknesses are the most glaring in the collection.

Doerr’s creative handling of the passage of time is just one of the qualities that gives the stories in The Shell Collector large scope. As the different type of lists attest, Doerr tackles a wide range of settings in his first collection. From the shores of Kenya to the wilds of Montana to coastal Maine and Oregon and suburban Boise, he returns to Africa only after taking the reader on a whirlwind tour. In each place, the locale and its characters are effortlessly described, as though from the perspective of a native rather than that of a writer researching the background for his work. Doerr uses scraps of foreign languages skillfully as well. When Dr. Kabiru examines the strange woman the shell collector has found wandering the beach, he announces, “a fever has her” and it seems a perfect translation. The reader can almost hear the Belorussion border post police chief, who interrogates the American anglers, describe the fish they have yet to catch. He taunts, “Oh yes. There are trouts, big trouts in Biebzra. He said something to his men and they repeated, Big trouts, and showed the Americans how big with their hands.” The reader cannot help but feel confident that the writer has given accurate depictions of these settings. They are all realistic, from Lamu with its Muslim mwadhini who begs the shell collector to heal his daughter, to an Idaho chain-grocery with its pudgy butcher named Duck.

Since he deals with such a disparate set of locations and stories, it is odd that Doerr seems to recycle imagery throughout the collection. The vivid description of a “tea-colored river” loses some of its strength because it is repeated in two different stories. Doerr describes stars and the night-sky gorgeously, but so often that it seems as though they must have been at the top of some sort of writer’s checklist. In one story the stars are “knife points,” in another, “fish hooks.” In one they “riot in the sky,” in another they “send a frail light onto the sea” and later “blaze in their lightless tracts.”

Another of Doerr’s obsessions is intestines, and in particular the words “viscera” and “eviscerate,” which appear repeatedly throughout the collection.

Doerr seems to be trying to connect his stories together by using smaller details rather than larger themes, uniting disparate characters and settings under the same sky that alters slightly to inform the particular situation. It’s an interesting goal, but here the device seems more of an accidental weakness than a consciously used tool, as though the writer reconsiders stars and disembowelment again and again because he cannot think of anything better to relate to the setting at hand. These repetitions hinder what would otherwise be an enormous breadth of material and are disappointing because Doerr’s underlying themes link his stories together in far more complicated and interesting ways. Both “The Hunter’s Wife” and “Mkondo,” for example, are stories about estranged couples who, by the last paragraph, find themselves reunited and on the brink of reconciliation.

Doerr’s breadth of setting allows him to illustrate well the difficulties a foreigner experiences in a foreign land. In “Mkondo,” for example, archaeologist Ward Beach must acclimate to Tanzania while he is working on a dig. When he brings Naima home with him to be his wife, she struggles to get used to the life of a suburban Ohio homemaker in the same way that Joseph Saleeby battles through his first harsh winter in Oregan. Doroteo San Juan faces a similar culture shock when her family moves from Ohio to Maine, and “July Fourth” is one long look at Americans who feel impotent and out of place in Europe. These similarities tie the stories in Doerr’s collection together more tightly than his repeated phrases and images or even the constant and more apparent theme of fishing.

Even if its other stories were not breathtaking and beautiful, which they are, and even if its characters did not introduce the reader to a host of captivating lives, which they do, The Shell Collector would be valuable for its longest and most ambitious story, “The Caretaker.” Following Joseph Saleeby from his young adulthood in Liberia through the horrific experiences of his war-torn nation to his arrival as a political refugee in Oregon, it illustrates both the scope of which Doerr is capable and the compassion and understanding which with he creates his characters. Josephy Saleeby is so believable—his story rings so natural, so true—it seems impossible that a white American could have written his life. The most moving passages in the story describe Joseph burying the hearts of five beached whales in the hillside above the shore. Because he has been unable to lay to rest any of the nightmares he witnessed in Liberia, this is a thrilling depiction of psychological self-preservation that becomes complete when Joseph eats a melon grown from the fertilized soil. For a 28-year-old writer to attempt a story with the geographical and cultural scope of “The Caretaker” requires enormous mettle; the story is indisputably a daring piece of work. Saleeby’s story is a triumph; and for that, we can and must forgive Anthony Doerr his small faults.