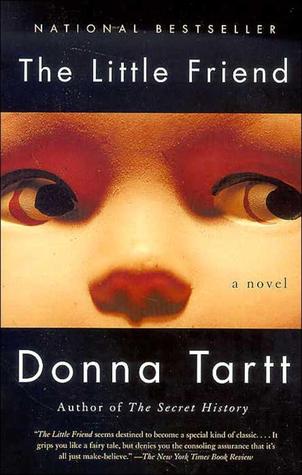

Writers, like pop stars, are often one-hit wonders. Assignation to this category seemed to be the fate of Donna Tartt, whose intellectual thriller The Secret History was published in 1992. That book describes a group of classics students at a tiny New England college, whose activities include “the search for truth and beauty.” They drink enough to make Hemingway proud and get caught up in two murders. The novel’s blend of cultural sophistication and page-turning crime captivated the general public and the literati alike. After ten years, Tartt has almost delivered on their hopes for a worthy second novel. But The Little Friend deserves a better editor.

The Mississippi-born Tartt has set her story in a small town in her home state, populated by impoverished blacks, whites in trailer parks, snake-handling preachers, and a dying circle of aristocrats. The protagonist of the novel, Harriet Cleve Dufresnes, is a member of the latter group. Her brother, Robin, was brutally murdered when Harriet was still a baby. The summer of her twelfth year, Harriet decides to solve and avenge Robin’s murder. A few chance remarks by her family’s housekeeper lead her to pin the murder on Danny Ratliff, who is somewhat unwillingly following in the criminal footsteps of his father and brothers. Harriet plays the sleuth through the bulk of the novel, as the Cleves and Ratliffs get to know each other a little too well. All of it is quite predictable.

Though she writes beautiful sentences and the occasional thrilling scene, Tartt has lost the seductive power of The Secret History. Both novels are approximately 500 pages, but only The Little Friend drags. Many of its main players are undeveloped. The dead boy Robin is among Tartt’s most three-dimensional characters, yet he appears only in the stories passed down by the Cleve family. Describing these stories, Tartt writes, “this clarity was deceptive, lending treacherous verisimilitude to what was largely a fabular whole, for in other places the story was worn nearly transparent, radiant but oddly featureless.” Gaudy language can’t hide the blandness.

I couldn’t help wishing that Tartt had turned away from Harriet and focused her story on Danny Ratliff. He alone among the characters grows throughout the novel. Aching to change but lacking the courage, he is more human, more real, than Harriet and her family. But he is easily manipulated. At the end of Harriet’s fruitless quest—if it can be called an end—she muses on ways in which she can work Danny into a tale that promotes the idea of her own heroism: “rich possibilities of story began to open like poisonous flowers all around her.” The effect is chilling.

But this book should amount to more than the summer adventures of a little girl. In parts it’s a coming-of-age story, a portrait of the decaying South, an exploration of race and racism, and a meditation on the effects of time. But none of these themes is allowed the chance to develop fully.

The end leaves you hanging, though you probably won’t care what happens to Harriet and her family. If you’re looking for a true successor to The Secret History, your wait is far from over.