In response to Anita Brookner’s third novel, critic Caryn James referred to what had at that point become “the predictable Anita Brookner heroine,” a stifled, passive woman resembling “a Victorian maiden who has stepped into the present.” Nineteen years, nineteen novels, and nineteen faux-Victorian-maidens later, predictability has hardened to inevitability, with the surprisingly negligible allowance that the heroine will sometimes be a hero. The relentless homogeneity of Brookner’s subject matter has by now become as noteworthy to the book world as have the finely crafted books themselves.

Over the course of her stunningly prolific career, the repetitiveness of the commentary has rivaled that of the fiction, as each year’s novel makes the group’s uniformity even harder to ignore. Early on, Michiko Kakutani wrote that Brookner’s characters are “an immediately recognizable type.” Before long, Carol Kino quipped that “in two shakes of a Dunhill fountain pen, we’re back to familiar territory: the echoingly empty London flat,” and Jacqueline Carey went on to note that Brookner had written “book after book about loneliness, blighted hope and unfulfilled desire.” The echo became sufficiently striking for Goreau to confide that “many early admirers have come to feel, as her novels appear punctually year by year, that Brookner is writing the same book over and over again.”

All of which forces the question of what on earth Brookner could be thinking of, releasing a series of books open to such obvious criticism, even as her fourth novel won the Booker Prize and her mastery inspires respect in even those critics who wish she would move on. Surely such conspicuous repetition must be calculated?

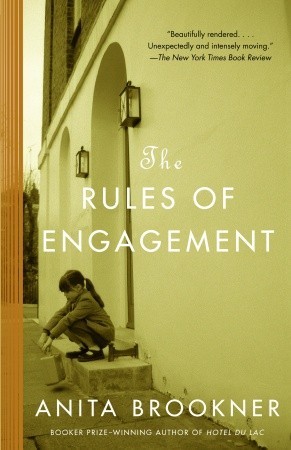

There is no denying the fact that the same world does in fact wait patiently behind each new cover or that the world in question is home to a succession of mute, forgotten characters and their impotent introspections, their antique decorum. This twenty-second iteration, The Rules of Engagement, offers no relief. It is about as inviting as a state hospital’s depression ward, not by any means a world we would care to inhabit. Yet our aversion is regrettably immaterial to the reality that it is, or at least is part of, the one we do inhabit. As Brookner’s latest narrator notes with typical dry lucidity, “Enlightenment would not be altogether welcome. But then it so rarely is.”

Brookner performs each year her not-altogether-welcome task with a grim sort of deftness, an accuracy unmistakable as it unfolds across measured, plot-barren chapters: for in rendering a slow, dim-lit existence with a sexless focus on proper behavior—a world of muted uniformity whose beauty lies in subtle tonal shifts—it is only appropriate (only a form of truth-telling, really) that the novels themselves should be placid, ruminative expanses whose beauty, which is considerable, lies in the small muffled shiftings of cyclical thought.

And it is in this very manner of consistency that Brookner ultimately comes to her own rescue; for if it is appropriate that each novel itself should in some sense embody the world of the novel, it is also fitting that the set of novels as a whole should take on that same uniformity-with-subtle-variation. Such a texture, Brookner insists, simply reflects the way things are. And indeed, Brookner is deeply committed to the way things are: she is fundamentally observant rather than creative, and the yearly yield of her unflinching accuracy seems more scrupulous record-keeping than unique invention. She is like one of her heroes, conscientiously marking the passage of time in the daily shifts of light across an empty London flat.

This disposition toward examination over imagination is one that Elizabeth, narrator and familiar Brooknerian heroine of The Rules of Engagement, recognizes in herself: “The time seemed to pass . . . but it was not the sort of time by which others reckoned.” It was “attentive to change . . . to tiny inconsequential happenings and accidents…[but] there was no narrative thread that I could invent.” Brookner herself does give us a narrative thread, albeit a slender one, as, for that matter, does Elizabeth, who is responsible for organizing and presenting her experiences. But in Brookner’s case (as in Elizabeth’s) the implication seems to be that no narrative is invented, per se, so much as real life is received and faithfully chronicled.

This holds true even when Elizabeth recounts as fact what must technically be conjecture: she often notes coolly the internal workings of other people’s heads, as if she were watching on a projector screen, but when now and then she primly reminds us that she can’t speak with perfect authority, we credit such skepticism just as little as she seems to. As with Brookner herself, we trust that Elizabeth, even in invention, will be accurate, accurate—both can be relied on to fabricate only true stories.

What story there is here largely concerns the relationship between Elizabeth and her oldest friend, a woman named Betsy, as it evolves and changes shape over the course of their lives. Betsy appears indeed to be Elizabeth’s only friend—at least apart from a few scattered phantoms from childhood or from her marriage, too alien to be granted faces, names, or more than one passing allusion—and their basic similarities make her an obvious foil for Elizabeth, a window into life’s other possibilities.

At every turn (or, as this is Brookner, at every sigh, every shifting of weight), the two line up against each other and then choose different directions. When they meet as children they are called by the same first name. To simplify matters, the other becomes

“Betsy,” an act and a name that fit her whimsical, self-inventive good nature, while Elizabeth remains “Elizabeth.” These young women are not cut out for giggly sleepovers and form a stilted, distinctly ungirlish alliance. But their formal discomfort comes from near-opposite circumstances. When they finish school, each spends time in Paris; Elizabeth passes long days on solitary walks, long nights in her rented room, while Betsy remakes herself as an intellectual, a revolutionary, a lover. Back in London, they become involved with the same married man; but while Elizabeth cannot sustain the affair, Betsy pours her last strength into being a woman he loves.

The contrast between Betsy’s open, idealistic sweetness and Elizabeth’s resolute clarity is where we find the moral focus for which Brookner is known. Betsy is constantly termed “good” and yet lies to herself, while Elizabeth is coldly, passively, helplessly perceptive, and it is because of this that Elizabeth emerges as the moral one of the pair. “That was the difference between Betsy and myself: I preferred to know the truth, however bleak, and what strength of character I had impelled me to look these facts in the face.” Corruption appears not as wickedness but as falseness in the plainest sense; Elizabeth is honorable in that she cannot, whatever her intentions, be other than she is.

No more can Brookner be other than she herself is; and no more, alas, can her twenty-third or twenty-fourth or thirty-second novel depart from the low-colored, bleak-skied world that is not her invention, but her discovery.