Sadly, it is one of the curses of their trade that great novelists often lead lives that resemble bad novels. Like a romance novel or a mystery, the literary pantheon is populated by stock characters, contrived and crassly predictable. The most familiar and glorified of the bunch are the Brilliant Recluses, followed shortly by the Drunks and the Academics, the Testoseronic and the Effeminate, the Rustics and the Socialites, and the newest members to the club, the Great Young Authors, the Prodigies. Most romantic of all, however, is the Great Forgotten Author.

As you may well know, from movies and the like, the myth goes as follows: a young passionate person endures all manner of hardship and neglect, toils thankless hours alone in a cramped space under candlelight, or flickering halogen, works numerous part-time jobs often involving hard physical labor, moves from city to city, boarding room to boarding room, gains scant recognition and far too late, and dies alone, penniless, with a smile on his face. And do you know why this person leads such a horrible, pitiful existence? Because he couldn’t help it; he was one of that rare species, nowadays nearly extinct, a TRUE WRITER. We need more like that one, we say, decades after his corpse has been interred. For we have been alerted to his work by some trusted visionary—like T.S. Eliot in the case of Herman Melville, or Vladimir Nabokov for Mikhail Lermontov. The deceased’s manuscripts are dusted off and re-published, finally receiving the respect and approbation the author so craved during his lifetime. It’s a beautiful story, one from which all indigent writers can find succor.

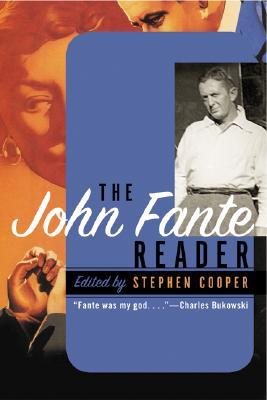

This is the story that Stephen Cooper, editor of The John Fante Reader, tries to tell. Or to sell, as it were. With the Reader, Cooper plays the part of trusted visionary, selecting the best of Fante, the Great Forgotten Author. The book compiles short stories and scenes from Fante’s novels, as well as letters he wrote to personages ranging from his mother to H.L. Mencken. The greater story that surfaces here—the story of this great forgotten author—is not, however, beautiful. It is devastating. For upon reading his letters, it turns out that not only did Fante receive insufficient recognition during his lifetime, but that from an early age, he was convinced that he was, in fact, a great writer.

The tragedy is that he was right. Why then, we might ask, did he fail? One popular reason advanced by literary critics has been the awkward timing of his birth—1909. He was too young to leave the country with the Lost Generation, but was a middle-aged square by the time the Beats came into vogue. A strictly historical explanation, though less poetic, is nevertheless more persuasive: he began writing in the leanest years of the Great Depression, perhaps the era of this country’s history most unfriendly to young writers. To earn enough to eat, Fante began selling scripts to radio and then movie studios. “I am now a complete and ungarnished hack,” he writes in a letter dated 1938. “I can turn the stuff out hanging from a four story building by one foot, and writing with the toes of my other foot.” His lack of financial success with his serious work kept him writing for the movies, ungarnished hack-work all of it. As might be expected from the sympathetic Cooper, he spares us this, the largest section of the Fante oeuvre, entirely.

Yet it is the spirit of the Depression and the lurking theme of failure that give Fante’s fiction its brutality. And brutality, after all, is what Fante does best. Brutality bred by futility and failure is the subject of the best story of the entire collection, an excerpt from Fante’s novel Ask the Dust. The set-up is highly autobiographical: Arturo Bandini, an Italian-American kid living in Los Angeles and trying to become a great writer goes to a diner one night with his last nickel. The beautiful “Mayan” waitress, who is his age, seems to be laughing at him. In his dejection and piqued self-consciousness, he thinks she is mocking him. In return, he draws attention to her worn huarache sandals, which betray a poverty of which she is ashamed. They hate each other and part with a fierce exchange. “I hope you die of heart failure,” she tells him. Later, alone at home, he realizes he loves the girl. The next day he leaves for her a story he had written, his best one. When he returns that night, she has been smitten; he recoils, and then, in a classically romantic plot turn, she chases him down on the sidewalk, begging him to meet her again. They each requite their love and our hero will get the girl on his own terms, having wooed her with the genius of his art. Then, as the lovers part again, like Romeo and Juliet after the balcony scene, this happens:

“Camilla!” I said. “Wait. Just a minute!”

We ran toward each other, meeting halfway.

“Hurry!” she said. “They’ll fire me.”

I glanced at her feet. She sensed it coming and I felt her recoiling from me. Now a good feeling rushed through me, a coolness, a newness like new skin. I spoke slowly.

“Those huaraches—do you have to wear them, Camilla? Do you have to emphasize the fact that you always were and always will be a filthy little Greaser?”

The reader cannot help but react as Camilla does—“in horror…Clasping both hands against her mouth, she rushed inside the saloon. I heard her moaning, ‘Oh, oh, oh.’” Even more brutal is the conclusion, in which Arturo triumphs in a racist, patriotic apotheosis, boasting of his solidarity with the Americans who had “carved an empire” where Camilla’s people had failed. The irony of this rant is fairly evident—the Italian Arturo is as American and as impoverished as Camilla; nevertheless, the sheer bitterness of Arturo’s voice and the violence of the self-abuse he unleashes are so disarming that the story is elegantly beautiful in its fury.

His prose, too, revels in its poverty. Fante writes sparingly, in a style that prefigures the Beats though with greater economy. Sentences which masquerade as tautology, on closer study, assume a kind of happy precision impossible to imagine with conventional prose. “My mother in the kitchen at that moment was not my mother.” he writes, for example. Or: “Other times I did other things.” A story begins with the line, “The day after I destroyed the women I wished I had not destroyed them,” (we don’t learn anything more about these women). Other dull violations of Strunk and White, like the absence of a referent, create similar, surprisingly rich, results. This is Arturo’s father, a recurrent figure: “He came along, kicking the deep stone. Here was a disgusted man. His name was Svevo Bandini, and he lived three blocks down that street.” We don’t know what street he’s talking about, but at the same time, we know pretty damn well what it looks like. In rare moments of elation Fante’s narrative is even liberated from grammar altogether: “her fur was silver fox, and she was a song across the sidewalk and inside the swinging doors, and I thought oh boy…”

Despite all this casting off—of family, of destiny, of grammar—Cooper finds it difficult to cast himself off from the collection; for although he has good intentions (writing terse, humble prefaces) and certainly does not mean to intrude, his selection of Fante’s work is marked by an ulterior motivation. Cooper’s collection may be a best-of, but at the same time, it is also the evidence for an argument he makes in the introduction: that Fante’s work is highly autobiographical. Hence the section of letters which concludes the Reader, and which correspond evenly to the seemingly autobiographical episodes selected from his novels and short story collections. It might come as little surprise then to learn that Cooper is also Fante’s biographer. Full of Life: A Biography of John Fante was published two years ago. Perhaps he found that the biography of a lost writer sells only if the writer’s work has been rediscovered first.

Though Cooper and his publishers cannot be reproved too much. His thesis, although utterly irrelevant to an appreciation of Fante’s work, is ultimately convincing. And Cooper ought to be credited for refusing to shy away from the places where the brutality of Fante’s literature crosses over into his real life. When it surfaces in his letters this brutality feels cheapened. Fante’s character, especially late in life, seems to lack the grave emotional complexity of his young protagonists. The most crude moment in this final section comes in a letter to his son Danny that Fante writes while working on a film in Italy: “I hate to say it, but I’m stiffening up like all old clods,” he writes. “I see lots of broads I’d like to bed down, but it’s just a kind of dreamy notion which quickly passes. I’ll take your Mother any day…” It’s probably not the kind of thing little Danny would have wanted to hear from his dad, nor is the final sentence quite convincing. After reading a whole mass of short stories about Joyce Fante’s suffering through childbearing and John’s infidelities (perhaps fictional, but he does use their real names in these stories), this show of machismo bravado to his own son made me want to react, again, as Camilla does.

Still, Fante has our sympathy in the end. In the collection’s last letter, written in 1981, two years before his death, we realize that Fante not only clung to the belief that he was a great writer, but even to the belief that he was a great young writer. He still felt young, his voice fresh, brazen. All this despite going blind due to complications of diabetes and with both legs amputated because of gangrene. In the letter, dictated to Joyce and addressed to an aunt, he writes at one point, “I am twenty-six years old.” It’s hard not to be convinced.