Since the birth of his mentally handicapped son Hikari more than 30 years ago, Kenzaburo Oe has often drawn on the challenge of raising the boy for literary inspiration. Several of the Nobel Prize-winning author’s well-known works—namely A Personal Matter, My Deluged Soul, and the two-volume Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness—arose from his own personal struggles as both a father and a son. The highly autobiographical O Rouse Up, Young Men of the New Age, translated into English this past year, returns to such themes. Completed shortly before Hikari’s twentieth birthday in 1983, O Rouse Up differs from Oe’s earlier works in that rather than grappling to accept Hikari into his family, Oe now documents his struggle to let the boy go.

While it can be said that many authors write themselves into their fictional works—it’s not just a coincidence that all of Philip Roth’s stories take place in Newark—Oe pushes this blurring of fiction and memoir to the limits. O Rouse Up’s unnamed narrator (referred to as “K” by the book jacket) is not just modeled after Oe, but actually appears to be an unflinching self-portrait of the author. Both Oe and his alter ego K are award-winning Japanese authors; both grew up in rural villages, majored in French literature at Tokyo University, taught school in Mexico. And most importantly, both men face the challenge of raising a mentally handicapped son named Hikari. It is difficult to separate Oe and K, and more likely Oe does not wish us to do so. This book is very much an author’s struggle to put his inner turmoil into words, to share something personal with the world.

The story opens with K returning from a business trip to learn that Hikari, whom he refers to by the childish nickname “Eeyore,” has been behaving strangely, threatening his family members with a knife and insisting that his father is not on a trip, but has died. K realizes that Eeyore is grappling with the realization that someday his father will die, and no longer be there to care for him and protect him from the world. From this realization comes, it seems, the basis of the book. K wonders,

Since my son had begun to ponder, with his

own kind of urgency, what would

happen following my death, was I not obliged

as his father to prepare him,

unflinchingly and without falling into idleness,

for his relationship to the world,

society, and mankind after that

inevitable moment had arrived?

K’s thoughts are perhaps typical of a father desiring to prepare his son for the future, but his task is made more daunting by his difficulty in establishing a true connection with Eeyore. Eeyore may have the body of a man—complete with violent and sexual urges—but he has the mind of a damaged child. The well-read and multilingual K exhibits an impressive command of literature from around the world, yet he cannot satisfactorily communicate with his eldest son. Eeyore can speak and answer questions, but it is difficult to ascertain whether or not he truly understands the world around him. Eeyore’s speech is always italicized, set apart from the rest of the text, giving one the impression that the lines are shouted or delivered in monotone. This heightens the idea that Eeyore’s speech is mechanical, without feeling or understanding.

K wants to relate to Eeyore both as a father and as an artist. He becomes obsessed with knowing if his son dreams or is capable of creativity, two things important to K as an artist. “Because I happen to be Eeyore’s father, and dreams have a role in my profession. So it’s only for me to want my son to have at least some capacity to dream!” he exclaims to himself. He must watch his attempts to reach Eeyore through his own art falter. K constantly dwells on his long-term goal to write a book of “definitions” that will explain the world to Eeyore in terms that he will understand, so that he may be better prepared to live on his own. His ultimate failure to write this book comes symbolize the times in the past when K could not protect his son, and he must reconcile himself to the fact that he will not be able to do so in the future, either.

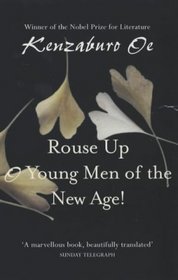

It is impossible to discuss O Rouse Up without mentioning William Blake, who provides the book’s title, chapter headings, and cover art, as well as much of Oe’s creative inspiration. Blake is tied to the two things that consume K: writing and his son. K claims to have used many of Blake’s metaphors in his writing, and turned to Blake’s poetry for guidance when Eeyore was born. Now he returns to them again as he faces losing Eeyore to the world. Scarcely a page goes by without a reference to a line from Blake’s poetry, particularly Blake’s Prophecies, which K first encounters in a serendipitous meeting with a crazy autodidact in college. Oe’s intelligent and fascinating discussion of Blake’s works, particularly his Prophecies, become one of the strongest features of the book. Not only does he provide helpful interpretations of some very difficult pieces of poetry, he also connects Blake’s words and images to his own life and relationship to his son. Oe’s expansive prose includes various seemingly miscellaneous memories and musings, which would appear to have little in common except they often spark an association in K’s mind with something he has read by Blake; thus Blake forms the backbone of the book, tying together what could have been many loose, aimless strands.

To call O Rouse Up a novel is to oversimplify the work, which exceeds the boundaries of the genre. It expands beyond the realm of a mere novel, appearing as more of a collection of memories, anecdotes, essays, and passage explications all under the guise of a single story about Hikari’s impending passage into adulthood. While this makes O Rouse Up much broader in its scope, it is also book’s greatest weakness. It can be overwhelming, and Oe offers little guidance through his meandering text.

This book was written, it seems, for the author as much as for the audience. At times it can be quite frustrating to keep track of the numerous events mentioned in the book, which are arranged thematically, rather than chronologically—making it nearly impossible to trace a single coherent plot. Revelations arrive without warning as they occur to K according to a logic that is not always accessible to an outside audience. The reader is truly at the mercy of Oe’s own thought process.

Despite this free-flowing, loose structure, Oe’s focus can at times be claustrophobically centered on his relationship to his son. Oe pays little attention to the rest of his family. K never names his wife or other two children, referring to them instead as “my wife,” “Eeyore’s brother,” “Eeyore’s sister.” While this practice effectively illustrates how Eeyore’s presence has dominated the family, at times it reads as an oversight. Oe’s examination of his relationship borders on an obsession, and Eeyore can sometimes be a tiring character. At times, some respite from both is needed and I couldn’t help but wonder how the book could have been expanded to consider Oe’s relationships with his other children.

Yet despite these weaknesses, O Rouse Up is worth reading simply because it is so well written. Oe’s descriptions of events are at times breath-taking and delicate, such as his description of K’s attempts to teach Eeyore to swim:

Sometimes I put my goggles on and swam along

side to coach him along:

underwater, his movements were calm, so very

calm that I could see his deep-set,

oval eyes open wide in an expression of quiet

wonder and could see each bubble

from his nose and mouth as it rose glintingly to

the surface.

What is even more amazing about Oe’s prose is that although many of the events are drawn from his own experience, Oe fictionalizes them, transforming the concrete into the surreal. This is partially due to his languid writing style, which causes a suspension of movement, adding weight to even the most mundane detail. It is also a result of his turning his life into a series of literary references. For instance, when K suffers from gout, Eeyore becomes fascinated with his father’s foot, a rather strange scene that takes on almost divine undertones when K connects this with Blake’s epic Milton, in which the soul of the poet enters Blake through his heel. While the connections between Blake and daily life can at times feel slightly strained, for the most part they are ingenious and even beautiful.

In addition, while the events may be presented somewhat randomly, all of his anecdotes are interesting, ranging from the poignant—such as the production of Gulliver’s Travels by Eeyore’s school—to the bizarre, including Eeyore’s kidnapping by a disgruntled graduate student or his rescue from drowning by a physically deformed former-Olympian. Furthermore, Oe sometimes broadens his narrative by incorporating events from Japanese history, such as the bombing of Hiroshima and the highly-publicized suicide of the writer known as “M” neatly into his own personal tale.

It is no accident that the first words of Blake Oe ever reads are two lines from the Prophecies: “That Man should Labour & sorrow & learn & forget, & return/ To the dark valley from when he came and begin his labours anew.” These words become something of K’s mantra, and are perhaps the best way to characterize his feelings in O Rouse Up, as well as the reader’s experience. By making K such an accurate reflection of himself, Oe makes it clear that he intends to write about life—his life. Faced suddenly with a grown-up son, Oe has trouble unwrapping his own thoughts, and this struggle is reflected in his unstructured writing. The reader is sometimes left adrift because Oe feels lost; the reader becomes frustrated with Hikari because Oe had a difficult time raising him. Since the book blurs the line between truth and fiction, the story—like life—reduces to a series of episodes, a mixture of thought and action, and Oe pulls the reader along as he endeavors to understand them.