The twentieth-century illustrator John Held, Jr., perhaps most famous for his depictions of the Jazz Age, was also a talented maker of imaginative maps. On his 1928 Map of Americana, which illustrates the pit-stops (“Gas Station / Rest Room / Hot Dogs / Orange Drink”) one makes on a road trip, he proclaims, “After All, No One Makes Maps Quite As Well As John Held JR, try as they might.” Such bravura appears in many of Held’s humorous maps, especially within legends meant to define the relationship between a map and the real world. In his Map of an Imaginary Estate for an Inveterate Fly-Fisherman, inter-connected pools and rivers cover a private wooded landscape. The “Fly-Tying Department” is an industrial city with smokestacks and turreted towers. A note at the bottom reads “A Scale of Miles: As Though It Meant Anything.” In another map Held wrote, “The scale is nobody’s business;” on another, “One of the charms of a map like this is that nothing is any where near correct. What are you going to do about it?”

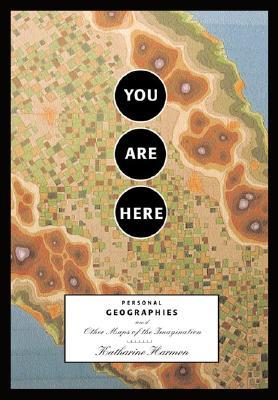

This bald-faced disregard for realism is what most characterizes the maps in Katherine Harmon’s You Are Here: Personal Geographies and Other Maps of the Imagination. From maps of Life and Love, to maps of dreamworlds and sitcoms and novels, to maps that illustrate perspective and emotion, Harmon’s selections ask us to consider just what makes a map an accurate depiction of the world and if accuracy really matters at all. Beautifully printed with hundreds of full-color illustrations, You Are Here is a loosely-tied-together collection of essays, quotations, and musings about maps that offers no concrete answers to the questions it poses. Instead, it becomes a kind of choose-your-own-adventure for the reader. It asks us to make connections and posit our own theories as we go, unguided by an underlying thesis.

The absence of an authorial argument is evident in the structure of the book, which Harmon divides into three rather un-balanced sections: Personal Geography, At Home in the World, and Realms of Fantasy. The book’s first section begins with ruminations on maps and navigation in an essay by Stephen S. Hall. After reminiscing about a childhood orienteering experience (orienteering being the “competitive sport of finding one’s way on foot across rough country with the aid of map and compass”), he suggests that a “more personal, more historical, more associative, more metaphorical, perhaps more spiritual” process might be what he dubs “orientating.” Orientating “begins with geography, but . . . reflects a need of the conscious, self-aware organism for a kind of transcendent orientation that asks not just where am I, but where do I fit in this landscape? Where have I been? Where shall I go, and what values will I pack for the trip? What culture of knowledge allows me to know what I know, which is often another way of knowing where I am?” These questions provide for a good deal more thought and investigation into the idea of mapping than Harmon’s own cursory introduction, which describes the project of the book as her “own personal proof of the mapping instinct” which, “like our opposable thumbs,” she asserts, “is part of what makes us human.” A more interesting proposal with which to explore You Are Here is Hall’s claim that “We are all creating our private maps. Like Mercator, we are not discovering entirely new worlds; rather, we are laying a new set of lines down on a known but changing world, arranging and rearranging metaphysical rhumbs [compass points] that we associate with successful navigation. To each, her or his private meridians. To each, a unique projection.”

The second essay, a creative non-fiction piece by Bridget Booher entitled Body Map of My Life, is a series of descriptions of physical scars (from biopsies and childhood accidents) and psychological scars, like this one:

5.

Location: Equal parts head and heart.

Cause: First crush in college (clean-cut preppy) suddenly stops calling and appears at parties with a shiny, diminutive Southern belle.

Diagnosis: Bruised ego.

Treatment: Learned to play quarters with (not so clean-cut) members of Beta Phi Zeta fraternity.

Follow-up: Later learned that freshman flame became a dentist in Pittsburgh. No regrets.

It’s an amusing exercise but perhaps one that is best left to a high school creative writing class. Booher’s piece is witty in its wry depictions of past physical and emotional pain, but interesting more for the associations the reader makes in trying to imagine his or her own history as a series of cartographic legends. There are some personal geographies, it seems, that are just too personal for public consumption.

Except for Hall’s contribution, which approaches the real concerns of this book head on, Harmon’s choice of quotations and essays in You Are Here seems more an awkward cobbling together of disparate elements than a coherent, organized compilation. Like Booher’s superficial investigation of a “body map,” many of the pieces almost inhibit a deeper, philosophical analysis of imaginative maps. I wished Harmon had taken her book in one of two directions by either expanding it into a fuller anthology of illustrations and serious writings or cutting out the essays, quotations, and chapter divisions all together, leaving behind an entire book of well-captioned, thought-provoking illustrations.

It is, after all, the illustrations in this book that make it fascinating. Harmon’s choice of maps and her careful attention to their order throughout the book invites dialogues between them. For example, a German palm-reading chart from 1480 faces a scarred hand drawn by a seven-year-old from Northern Ireland for a project that “investigat[ed] the uses of mapping for generating creativity and change.” A dream map of the Siberian Chukchi people faces a ritualistic vision map from the Amazonian Turkano Indians. A series of evangelical maps from the nineteenth century visualize the spiritual path all souls wander and the obstacles and dangers they meet along the way. These maps depict, among other things, The Falls of Eternal Despair, The Impenetrable Hedge of Sin, Hypocrisy Heights, Purity Falls, and Embezzle City.

Perhaps the most coherent series is a set of seven maps which document different historical perspectives on love, passion, and marriage . The anonymous 1772 New Map of the Land of Matrimony,(which Harmon reproduces courtesy of the Map Collection at Yale, many of whose maps can be viewed online) is a delicate engraving mottled with waterstains. In the Land of Matrimony, the Temple of Hymen overlooks Bride’s Bay. Across the Ocean of Love, in Friesland, the city of Singletonn is situated on an isthmus nestled between the twin islands of Coquet and Prude. Contrast this more seriously cartographic endeavor with Ernest Dudley Chase’s 1943 A Pictorial Map of Loveland–a huge, multi-lobed pink heart on which round-faced cartoon couples disport themselves in absurdly alliterated locations like “Melody Mountain” and “Lustrous Lake,” or beside punning toponyms like the golf course called “Fore-Ever,” or the “I’m Telling U Strait.”

The 1960 version of the Love Map appeared in McCall’s Magazine as two heart-shaped landscapes: the Geographical Guide to a Man’s Heart with Obstacles and Entrances Clearly Marked and the Geographical Guide to a Woman’s Heart Emphasizing Points of Interest to the Romantic Traveler. These maps, which show how to reach the Walled City of the Real Him on one hand (by fording the Memory of Mother Moat, circumventing the Province of Preoccupation with a Pretty Face, and finding an alternative entrance to the Impenetrable Wall of Ego) or the Hidden City of the Real Her (by avoiding the Swampland of Sentimentality, and steering clear of Dear John’s Junction and the Sound of Her Own Voice) on the other. Entertaining for their catchy place-names, these maps are also enormously illuminating representations of the era’s expected gender roles. The “clearly marked” entrances to the man’s heart include the Avenue of Beauty, Homemaker’s Highway, and Hostess with the Mostest Avenue. The land’s largest province is the Territory of the Big Operator with its Blue Chip Mountains and Secretary Falls. In the woman’s heart, the River of the Good Homemaker is a tributary of the River of Femininity which runs directly past Children’s Corner in Mother Country. These maps make unmistakable what successful navigation of love and marriage means for each gender.

In his 1980 A Map of Lovemaking, Seymour Chwast uses the subtle color gradations and elevation circles we normally see on climate and contour maps in his cross-section of a male body and female body in coition. Chwast’s painting considers topology, the science of place, within the context of the body’s sexual sites. Anatomical designations run in plain black caps across the map, as though they were place-names—Testicle seems to be a town just outside Labia, and Uterus is a valley close to the mountainous region of Bladder. The man’s and woman’s large green colons are like verdant islands, identical structures that lie parallel across the flat grey “Gulf of Lust” between them. By placing it in sequence with Ernest Dudley Chase’s tacky map from the `40s, the moralistic eighteenth-century New Map of the Land of Matrimony, and the 1960 businessman/ homemaker pair, Harmon suggests that Chwast’s painting is our contemporary Map of Love. Abstractions like “Eternal Bliss” and “Perfect Harmony,” two spots on Chase’s map, have been replaced by the physical realities of the body, the Penis lying inside the Vagina, a fleeting moment of corporeal union that must suffice for Love and all the other expectations plotted onto those earlier geographies.

Robert Louis Stevenson began writing Treasure Island as a narrative unfolding on an imaginary map he had drawn. It was one of the first novels to include a map of its fictional landscape to aid and inspire readers, which sparked an on-going tradition of endpaper-maps that would come to include books as dissimilar as Winnie-the-Pooh and The Lord of the Rings. Harmon includes a short essay by Hugh Brogan on how this tradition manifested itself in Arthur Ransome’s 1930s adventure stories for children. (She also includes some of fantasy-cartographer Karen Wynn Fonstad’s maps of Middle-Earth, as well as a map of Mayberry, North Carolina, the fictional setting of The Andy Griffith Show.) For Stevenson, maps were objects of unlimited appeal. “The names, the shapes of the woodlands, the courses of the roads and rivers . . . here is an inexhaustible fund of interest for any man with eyes to see, or tuppenceworth of imagination to understand with.” Katherine Harmon’s achievement in You Are Here is to inspire in readers an appreciation of imaginative geographies. Reaching the end of her collection, we find ourselves agreeing with Robert Louis Stevenson when he wrote, “I am told there are people who do not care for maps, and I find it hard to believe.”