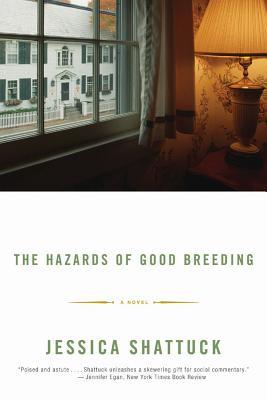

The English writer and literary critic G. K. Chesterton once said, “A child of seven is excited by being told that Tommy opened a door and saw a dragon. But a child of three is excited by being told that Tommy opened a door. Boys like romantic tales; but babies like realistic tales—because they find them romantic. In fact, a baby is about the only person, I should think, to whom a modern realistic novel could be read without boring him.” Perhaps Chesterton takes too hard a line on realistic fiction here. After all, our attention is often grabbed by stories about ordinary people doing ordinary things, without any hint of dragons or romance at all. I would argue, though, that those ordinary, realistic stories that we enjoy have something about them, a certain spark, that makes us see our own ordinary, cereal-for-breakfast existences in a new light. Realistic stories that mirror our daily lives but add no such new perspective are boring, however, and perhaps Chesterton is correct in saying that only babies can enjoy them. I predict Jessica Shattuck’s first novel, The Hazards of Good Breeding, will be a big hit with babies this year. It is a novel too filled with the stuff of our daily lives, too filled with product-placement and ordinary action, and too deficient in that spark that makes realistic fiction extraordinary, to interest the adult reading public.

The Hazards of Good Breeding tells the story of the Dunlap family, New England bluebloods who have lived in Concord for more than two centuries and are now in moral and spiritual, if not financial, decline. Jack Dunlap, the patriarch, is a hard-headed businessman who spends his spare time building Revolutionary War dioramas and breeding blue-heelers, dogs that are “part shepherd, part Border collie, part dingo.” Jack is a typically distant father, able neither to communicate effectively nor to show affection to his family. His ex-wife Faith divorced him after suffering a nervous breakdown that has left her, for the moment, incapable of caring for their youngest son Eliot, whom the narrator refers to as “the dregs of his parents’ conjugal activity.” Caroline, their only daughter, has recently graduated from Harvard. She returns home for the summer to try and hold the Dunlap family together and watch over ten-year-old Eliot. Her boarding-schoolmate Rock Coughlin hangs around the Dunlap house, smoking pot while trying to figure out what to do with his life after college and hoping he can finally win Caroline’s heart. Then there is Rosita, Eliot’s former babysitter and Jack’s sometime lover, who happens to be carrying his child.

The Dunlaps’ story unfolds over a period of days in the early summer, a period so brief, in fact, that its series of dramatic revelations and realizations seems rather implausible, especially for a novel that is set in an actual American town, and constantly refers to real places and products. Faith’s first visit back to Concord after her breakdown coincides with the arrival of Stephan, a film-maker who is shooting a documentary about Boston society. While Stephan tries to dig up dirt on Concord’s elite families, each of the Dunlaps, as well as Rock Coughlin, is privately evaluating his life’s purpose and future goals. Working with Stephan on his film, Caroline begins to see her family and their peers from his perspective. She asks what happens if he does not find what he’s set out to find in a project: “Just what if it wasn’t how you pictured it or whatever?” He replies, “I guess that’s never happened to me. If I see it some way, then that’s what comes out in the picture. You just have to be careful not to overcomplicate, you know? You have to have a distinct vision of the thing and it comes through.” Caroline learns soon enough that Stephan’s “distinct vision” of her own family is not only inaccurate but sensational. Seeing this vision through the film-maker’s lens for a few days makes Caroline, and the reader, reconsider the Dunlaps’ identity.

The Hazards of Good Breeding is at times an awkwardly told tale. Shattuck makes repetitions that detract from, rather than complicate, the narrative. For example, more than once the vinyl seats of a car are “flesh-colored,” or a character describes an event as “almost tragic.” The novel is neither long enough nor complicated enough to justify these recurrences. They only make us wish Shattuck had tried a bit harder to use a larger vocabulary. Nevertheless, the author has a strong sense of the way a good story arcs from its outset to its climax and denouement and she feeds information to the reader in a way that makes us want to turn the page. As events begin to occur more rapidly, the novel improves, though not enough to compensate for Shattuck’s glaring omissions. For example, in the first few pages, the narrator mentions that Caroline has recently broken up with Dan, her college boyfriend of two years. Neither Dan nor their long-term relationship is mentioned again in the novel, an omission that makes the detail itself seem misplaced and unbelievable. Stephan’s plot, embedded within the Dunlaps’ story, is disappointing because it clearly only serves as a mechanism to provoke Caroline’s reevaluation and subsequent defense of her family. As the rather uncomplicated villain of the story, Stephan is more of an embodied plot device than a full-fledged character. When he disappears from the narrative immediately after the climax, it is with the minimum explanation possible, making us wonder why he was even there in the first place.

What is most frustrating about Shattuck’s novel, and what makes it ultimately so tiresome, is its inability to really flesh out the other members of the Dunlap’s well-heeled peer-group. While Jack and Caroline, Faith and Eliot, become three-dimensional characters with plausible psychologies over the course of the story, the rest of Concord’s elite are defined merely by their pink polo shirts and preppy pedigrees. Describing the guests at a country club wedding, the narrator smugly reviles the “boys Caroline grew up with who are in their mid-twenties now, well launched into inevitable futures of gradual hair loss, back problems, and knee surgery; of cool, polite marriages to blond girls whose health and athletic prowess has everyone fooled, for a brief window of time, into calling them pretty; of desperate, distraction-seeking love affairs with golf, paddle tennis, squash, and backgammon; of memberships at the Ponkatawset Club and coat-and-tie thirtieth birthday parties; of having the same conversations with the same people in the same mind-numbingly dull places forever.” Criticizing Concord’s upper-crust with these sorts of generalizations is not only mind-numbingly dull itself, it is also far too easy an escape, especially for a novel that sets out to defy the intended conclusion of Stephan’s documentary: that all affluent families are the same and that the degenerate upper class is a self-caricature to be laughed at.

If Caroline Dunlap is disappointed to learn that the slick documentary-film-maker always finds exactly what he proposes to find in his films, that he never cares to complicate his “distinct vision,” then we as readers are disappointed to learn that Jessica Shattuck is comfortable pigeon-holing her more peripheral characters as the “personalityless drones” Caroline despises. The Hazards of Good Breeding seeks to probe through the Dunlap family’s WASPy exterior to discover both the deep flaws and also the great courage and honor that lie behind it. Unfortunately, Shattuck fails to attempt the same for the rest of Concord society. Her vision of the subject is only slightly less narrow-minded and schematic than Stephan’s and the inconsistency of her portrayal makes her unredeemably clumsy as a social critic. At the wedding, Caroline remembers the last time she saw the groom: “he was coming out of the Harvard Club wearing a yellow V-neck sweater with a pink-collared shirt tucked into it like a pair of pig’s ears.” The narrator’s complaints about privilege make even pastels seem somehow incriminating, A novel that distinctly fails at the project it sets out for itself, as The Hazards of Good Breeding certainly does at serious social observation, has little value as a whole.

Like many first-time novelists, Shattuck works her own experience, at least parts of it, into her fiction. It is no surprise, for example, after reading a novel in which the H-word seems to rear its ugly crimson head on almost every other page, to learn that its author grew up in Cambridge and attended Harvard herself. Her depiction of old school New England affluence and its conservative conformity, however, seems studied rather than natural. She hasn’t quite captured the lingo of real preppies, who would never say “Middlebury College” instead of Middlebury, or “The Independent School League” instead of the I.S.L. Shattuck’s details are like foregone conclusions because they are completely, and disappointingly, unoriginal. Of course the Dunlap twins played hockey at Harvard. Of course Faith’s peers are catty women who spend their time playing golf and tennis at the club. And of course all the men wear pink polo shirts and blue blazers. Many Yalies might nod in recognition when Caroline is described as “twenty-two now, and out of college—of Harvard? (When asked where, she answers as if the question mark belongs, as if, maybe, it might be unfamiliar, and now the question mark seems intrinsic to the place itself, as if, maybe if her father hadn’t gone, and his father hadn’t gone, and his father’s father before that, she wouldn’t have gotten in.)” In spite of the novel’s few strong moments, reading The Hazards of Good Breeding might make one want to revise that age-old advice for young writers, “write what you know.” Yes, write what you know. But if what you know is Harvard and the angst of being a privileged, misunderstood WASP, find more interesting material.