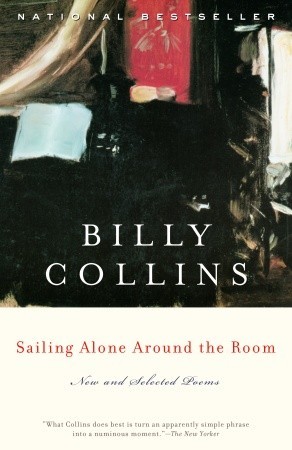

Billy Collins’ poetry has long been described as “accessible”—a term that has been used as both a compliment and a disparagement. There is no doubt that the simplicity of his language and the applicability of his everyday subject matter make Collins’ poetry interesting and approachable to a wide range of readers. For his devotees, Billy Collins’ brilliance lies in this straightforwardness and its ability to captivate people who are completely unfamiliar with poetry. For his critics, however, his trademark plain language and common themes imply a kind of self-centered superficiality that, while attracting readers, fails in its poetic duty to create new understanding. Good or bad, Collins’ accessibility has brought him commercial success almost unprecedented for a living poet. In 1999 he signed a six-figure, three-book deal with publishing giant Random House, the result of which is his first collection of new and selected poems, Sailing Alone Around the Room. In addition to his popularity with readers, Billy Collins has also received recognition from his peers in the world of contemporary poetry, culminating in his appointment to the nation’s poet laureateship for 2001-2002. His new collection has arrived at the perfect moment to become the text by which Americans, both readers and reviewers, judge the work of their newest ambassador of poetry.

For those who are unfamiliar with Billy Collins, Sailing Alone Around the Room serves as a solid introduction. In addition to many of his most acclaimed poems from four previous collections, The Apple That Astonished Paris (1988), Questions About Angels (1991), The Art of Drowning (1995), and Picnic, Lightning (1998), twenty new poems give a glimpse of his more recent work. This collection compiles pieces written over a decade, and the poet’s preoccupations and recurring themes reveal themselves quite clearly within its pages. Collins’ poems are, in their essence, descriptions of his own imagination, his own meditations and musings. Rather than depicting the outside world, they use a point of departure, a familiar object or occurrence (like a Victoria’s Secret catalog or a pin-up calendar) to draw the reader into the world of the poet’s inner thoughts. In “Schoolsville,” Collins envisions all the students he has ever taught as the population of a small town where he is the mayor. His first-person narration helps the reader to follow his train of thought: “I can see it nestled in a paper landscape,/ chalk dust flurrying down in winter.” He goes on to describe the students in his made-up town:

On hot afternoons they sweat the final in the park and when it’s cold they shiver around stoves reading disorganized essays out loud. Collins continues a stanza later,

Their grades are sewn into their clotheslike references to Hawthorne. The A’s stroll along with other A’s. The D’s honk whenever they pass another D. The humor and precision of Collins’ images makes the landscape of “Schoolsville” compelling and immediate.

“The Wires of the Night” also translates abstract, inner thoughts into comprehensible images but with beauty rather than wit. Kept up through the night by the loss of an unnamed man, Collins pictures his death first as a body, then as a house with “an entrance and an exit/ doors and stairs,” then as a “white shirt and baggy trousers,” then as a book, a car, a house again, a lover and a bed. The transformation of concrete images through the poem mirrors the emotional transformation of grieving and leads to the inspiring, if somewhat undemanding final lines:

and then [his death] was the light of day and the next day and all the days to follow, it moved into the future like the sharp tip of a pen moving across an empty page. In addition to setting his imagination to work on events in his own life, Billy Collins also contemplates external images and ideas. Sewn into the fabric of Collins’s poems like the grades of the students in “Schoolsville” are references to other writers and other works. Rather than creating a new interpretation of a theme first penned by Shakespeare or Wordsworth, however, Billy Collins’ work is less a reanalysis and more a translation of great literary works into modern colloquial English, almost a Clif’s Notes for poetry. In “Lines Composed Over Three Thousand Miles from Tintern Abbey,” from the 1998 collection Picnic, Lightning, Collins creates modern images for Wordsworth’s famous poem, and reduces it to a few simple lines of explanation:

I was here before, a long time ago, and now I am here again is an observation that occurs in poetry as frequently as rain occurs in life. “The place and the poet may be different,” he continues, “But the feeling is always the same./ It was better the first time./ This time is not nearly as good.” Collins’ language here is closer to a high school student’s poorly written essay than Wordsworth’s soaring “Lines Composed A Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey.” Indeed, throughout the entire collection his language deliberately mimics contemporary spoken English, with its slim vocabulary, dangling prepositions and confounding idiomatic expressions.

Billy Collins’ resistance to form and gorgeously wrought expression can be frustrating. The lack of traditionally “poetic” language in his poetry almost makes the reader feel like he is getting away with something he shouldn’t be, as though his expression is too easy to be art. But Billy Collins is sticking to a decided mission; while his poems are neither demanding nor complicated, their very simplicity and clarity are consciously crafted to assuage the qualms of unfamiliar readers. The key motivation behind his work is an attempt to promote the reading of poetry, and to place poetry in the context of Americans’ everyday lives. This promotion is not limited to his own work; his poems serve as instructions on how to incorporate any kind of poetry or writing into daily life. In “Japan,” Collins illustrates how to read a poem by describing the joy he finds in one particular haiku, identified as

the one about the one-ton temple bell with the moth sleeping on its surface. Reciting it while walking around his house feels like eating the same small, perfect grape again and again. As Collins’ recitation continues, his feelings about the haiku change as his understanding of it shifts. Saying it in front of the window, “the bell is the world/ and I am the moth resting there.” In front of the mirror, “I am the heavy bell/ and the moth is life with its papery wings.” Lying in bed that night, Collins finally brings the moth to life through his reading, until “it has flown/ from its line/ and moves like a hinge in the air above our bed.” Billy Collins’ poem about a poem blurs the line between a written image and its actual incarnation, demonstrating the way in which all readers should enjoy poetry: as sounds and words and, eventually, living, breathing things that expand experience.

Billy Collins is at his very best, however, when writing about the practice of writing. In providing a window into the way writers spend most of their lives he creates yet another means by which poetry can be brought into the space of everyday life. As readers begin to understand just how poets think and create they can better recognize the moments of inspiration in their own lives. In “Tuesday, June 4, 1991,” Collins describes the mundane details of the morning, remarking how it would all

quickly be forgotten were it not for my writing these few things down as I sit here empty-headed at the typewriter with a cup of coffee, light and sweet. There is no magic act of creation behind these words, Collins asserts, just a boring Tuesday morning and a description of the view outside his window. Describing the ordinary human details encompassed in his writer’s life, Billy Collins places poetry and writing in the context of the prosaic. For Collins, moments that inspire poetry are within everyone’s reach. In “American Sonnet” he calls “the picture postcard, a poem on vacation,” and compares all writers of postcards to poets, all recipients to readers of poetry. Collins makes a clever case for the postcard as a form by describing it as all poetry could be—“a few square inches of where we have strayed/ and a compression of what we feel.” When poetry finds its way into Americans’ ordinary worlds, Collins hopes, perhaps the “American sonnet,” or contemporary poetry in general, can be rejuvenated.

While Collins’ accessibility is a function of his simple language, humor and imagination, it also stems from the intimate relationship he establishes between the reader and himself. His use of the second person often applies to the reader and draws her immediately into the space of the poem. Collins relies on his reader, as constant silent observer, as witness, as lover and friend. In addition to wanting readers to understand poetry in an informal and powerful way, he wants to know and be known himself in the same manner. In “The Flight of the Reader,” the final poem of the collection, Billy Collins is concerned with the possible demise of his relationship with his most constant companion. He wonders if the reason the reader stays “perched on [his] shoulder” has something to do with his trademark, often-cited accessibility and his poetry’s resistance to profundity:

Is it because I do not pester you with the invisible gnats of meaning, never release the whippets of anxiety from their crates [?] He worries that the reader will vanish one day and he’ll be abandoned suddenly without anything left to say. Collins ends the collection by trying to deny his reliance on the reader:

It’s not like I have a crush on you and instead of writing my five-paragraph essay I am sailing paper airplanes across the room at you— it’s not that I can’t wait for the lunch bell to see your face again. It’s not like that. Not exactly. His insistence only proves his amorous affections, only strengthens the associations he makes in the final stanza. If Collins is the boy crafting paper airplanes to fly at his grade school sweetheart when he should be doing serious work, then the reader is the object of his affections and the recipient of those love letters.

While Billy Collins’ poetry is simple in its language and form and resists profound meaning and associations, its adamant mission to make a place for poetry in American life overcomes those inherent frailties. Billy Collins will have succeeded in his noble calling not if his poems remain popular but if poetry itself achieves an elevated and revived status. There can be no better poet for this task than a man who finds poetry in catalogues and calendars and boring Tuesday mornings, who sees sonnets in postcards and can describe a favorite haiku in ten different ways. Indeed, what better advocate of poetry could America have than a poet who sees himself as a lovestruck student, his poems as the paper airplanes that boy folds and flies at his darling, hoping to make a direct hit?