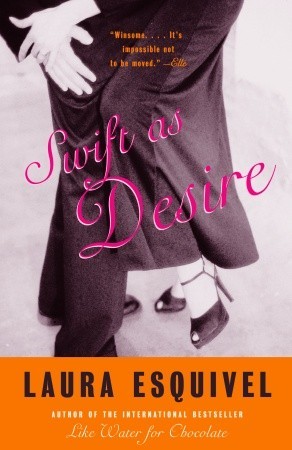

I was able to finish Laura Esquivel’s latest novel only because I loved her previous one, Like Water for Chocolate, a charming magical realist story about unsatisfied desires. Like Water for Chocolate was a beautifully written fairy tale that didn’t pretend to be anything more than entertainment. I slogged through Swift as Desire with the ultimately unrealized hope that Esquivel would match this delightful experience. Esquivel, however, apparently chose to make Swift as Desire a more serious novel, and it suffers for it. She attempts to weave Mayan mythology, modern science, and historical data into a romance story. The result reads like miscellaneous excerpts from high school textbooks, self-help books, and Popular Mechanics.

The plot is ostensibly about words, and how we communicate – or miscommunicate – in every day life. The main character of the story, Jubilo, has the unique gift of being able to decipher peoples’ unspoken desires. As a young boy, he serves as a translator for his Spanish-speaking mother and Mayan grandmother. By “mistranslating” their conversations, he was able to fix their troubled relationships. Years later, working as a telegraph operator, Jubilo continues to try to help people express their true feelings in words. Yet Jubilo is not always able to understand the true feelings of the person closest to him, his wife Lucha, and this eventually leads to the disintegration of their marriage. Unlike the consistent lightness of Like Water for Chocolate, everything about Swift as Desire is heavy handed. The prose ranges from the melodramatic – “Who could have warned him that he would end up lying in bed, in a near vegetable state and incapable of communicating with those around him? Who?” – to the mind-numbingly dull:

People hide their feelings from others, often behind pretty words, or silence them to avoid violating social conventions. The discordance between desires and words causes all kinds of communication problems and gives rise to a double standard both in individuals, who say one thing, yet do another.

At first such clumsiness could be attributed to a poor translation, but a comparison with the Spanish edition suggests that the original prose is just as ponderous.

The plot consists of several major (often uninteresting) incidents, followed by pages of analysis and proselytizing on subjects from the nature of love to the technology behind the telegraph system. The characters in the story do not develop but rather act in whatever way is convenient to propel the plot. Conversations do not resemble normal patterns of speech; in Esquivel’s world, a simple question can trigger the confession of one’s deepest secrets.

Jubilo’s miraculous gift is never deeply explored, nor is the tension between the Mayan and Spanish heritage. Ultimately, the reader is left quite unimpressed with Jubilo’s so-called “gift” because the story only focuses on the few occasions when it fails him (a phenomenon Equivel tries to demystify by attributing it to sunspots, as though Jubilo were nothing more than a cellular phone.) Jubilo, Esquivel shows, is doomed when he has the misfortune of being like the rest of us – forced to rely on his own instincts and knowledge of those around him. Having dismissed Jubilo’s talent, the novel s reduced to a rather mundane story about a man’s misunderstanding with his wife.

Despite the seductive title and the bodice-ripper, even the romantic elements of the story fail. One quickly grows weary of the relationship between Jubilo and his wife, which seems more pathetic than romantic. The two apparently married in order to have fabulous sex, with continues to drive the relationship for the rest of the story. Esquivel provides us with disturbingly unromantic descriptions of their physical intimacy, such as: “Jubilo had carefully mapped out his wife’s erogenous zones. He had catalogued her points of greatest sensitivity.” This clinical description of sex is in keeping with Esquivel’s general desire to demystify every aspect of her book.

Esquivel is much more compelling as a magical realist writer. The beauty of this genre is that people feel no need to demystify the supernatural. In Like Water for Chocolate, the cook’s emotions become part of the food she makes, infecting everyone with her feelings; the reader is spared any attempt to explain such a phenomenon, and this makes the story more interesting.

For some reason, Esquivel needs to give every mysterious event in Swift as Desire some kind of scientific or historical credibility. The story is often interrupted by long passages containing unilluminating scientific or historical data. Take for instance, the account of one of the many arguments between Jubilo and Lucha:

Usually Jubilo…understood why people said ‘I hate you’ instead of ‘I love you’ and vice versa. But now he kept misinterpreting the signals Lucha sent him. To Jubilo his wife was like the Enigma machine used by the Germans during World War II to send encoded messages. During the war, the radio served as an essential tool…

This non sequitur continues for several paragraphs before Esquivel returns to the actual story. It is difficult to be swept up in the passion of the story if it is constantly being interrupted in such a manner. Esquivel is a wonderful storyteller, and one wishes she would do just that: tell a story, no belabor it.

Even worse is Esquivel’s insistence on explaining every emotion, every silence, every gesture to her reader, as though she is afraid the audience will not understand how everything ties in to her overarching theme of language. Yet many of these ideas would actually be better off unspoken. In doubting her audience, Esquivel also doubts herself, as though an audience wouldn’t be able to glean the deeper meaning from the story. The unexplainable – and the romance – become unromantic.

Perhaps the problem with the book is that it is too much like real life. It is at times boring, random, repetitive, disorganized, and downright unpleasant. If Like Water for Chocolate was able to distill from life everything that is beautiful and mystical, Swift as Desire does just the opposite.