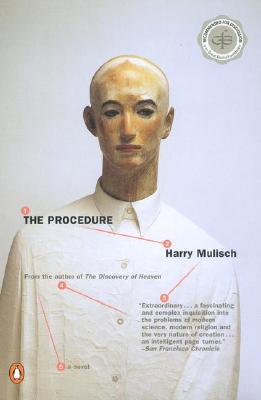

In the beginning, Harry Mulisch created The Procedure. And though it sounds much like a John Grisham paint-by-statutes legal thriller, it is something with infinitely greater ambition. Mulisch, author of The Discovery of Heaven, European literary darling and high priest of the novel of ideas, is never satisfied with the few conventional bones upon which modern fiction rests. Instead he builds a crazy quilt of ribs upon which he fleshes out a novel that takes as its subject the act of creation in all its forms. From Watson and Crick to Dostoyevsky to JHVH, he draws together the acts our society recognizes as “creative” in an elaborate meditation on how one can create and what it means to succeed or fail in doing so.

And Mulisch said: Let there be a Golem. And indeed, it would hardly fit into the contemporary literary landscape without one. From Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay to James Sturm’s The Golem’s Mighty Swing, 2001 is the Year of the Golem. In Jewish mystical writing, creating a living being from clay is the prerogative of God, but a facsimile can be formed by a person wise in the ways of the Torah and kabbalah. This being, the golem, serves all of these authors as a symbol of the double-edged power of creative excellence. In Mulisch’s case, the golem joins the novel when its early formative notions start to evolve into fictional objects, where the mysticism and philosophy of the first pages takes concrete shape. In this version of the venerable Jewish folk tale, Rabbi Jehudah Löw creates the Golem not to ward off angry Christians, but instead at the request of the Emperor, to avoid having his fickle anger light upon the head of the Jews. In order to do so, he has to recreate every possible permutation of the name of God. The rabbi discovers that even a successful act of creation can have unexpected side effects and disastrous results, and that the name of God is a fickle force.

And Mulisch said: Let there be a Maker. With Victor Werker, introduced nearly halfway into the novel, Mulisch finally sets up a main character. A microbiologist and aspiring Creator, he is the spiritual and physical descendent of Rabbi Löw. The one who works, who takes old material and shapes something which was not there before, is the fundamental creator in Mulisch’s universe. The pains he has taken to set up a dichotomy in which characters are both relentlessly predetermined and somehow live on their own result in Victor, who seems to be struggling to release himself from the page. Heavy with sorrow, Victor is trying to run away from his stillborn daughter and, at the same, towards her mother, who gave him up because of his inability to help her face the trauma of that aborted creation. Yet he gets nowhere on both fronts, unable to come to terms with either loss. Heretofore breathtakingly accelerated, the novel here brakes in midair, like Wile E. Coyote, and takes a nosedive. Suddenly, Mulisch is mired in the aftermath of Victor’s creation, which has taken place offstage, one whose details are frustratingly absent. Victor’s aimless musings are not nearly as interesting as his creator’s, in the beginning.

And Mulisch said: Let there be Science. Victor is a hard scientist who acts much more like an aesthete. Victor is a microbiologist, and he has (of course) created life, a small non-organic self-replicating creature he calls the eubiont. In so doing, he has started a whirlwind of controversy, which seems to occupy his thoughts much more than the nature of his actual research. Where most scientists would kvell over their breakthrough, or attempt to learn more, Victor seems most concerned with writing a book to make his work comprehensible to the man on the street. While this gives Mulisch a chance to compare DNA to the letter codes of the Bible, it also rings false. Mulisch is ignoring his character’s scientific origins, origins he expounds on at great length, and taking a cheap way out so that he does not have to explain the rather complicated problem of how Victor built his twenty-first-century golem. Ideas take over the novel, at the expense of the realistic development of the character who puts them forth.

And Mulisch said: Let there be Art. In addition, Mulisch, in what could only be called a subplot in a book of this ambition, attempts to reunite Science and Art. Mulisch includes a few too many of the names of God, and, like the rabbi’s golem, his work eventually crumbles as a result. As a serious look at the nature of creation, The Procedure is unparalleled. As a work of fiction, it leaves something to be desired. Too much to wonder at, and not enough exposition, for a novel of 230 pages. Nevertheless, the heights it reaches early on make it worthy of a readership.

And Mulisch said: Let there be Wittgenstein. And duly, reflection upon the nature of language and the necessity of words to creation initiates us into Mulisch’s formally personal world. The book eagerly invites serious philosophical questions about the possibility of ever creating anything truly novel. Casual reference is made to the existence of alternate timescapes whence plots and characters, concepts which seem to spring forth from human minds, are truly drawn. This is necessary, according to Mulisch, because the existence of even one letter while the work is being written implies the rest of the work, and as that completed work fails to exist at the time of its writing, according to our subjective worldview, there must be another universe in which it does. In passages like this, he skips jauntily from idea to idea, building up his own rococo structures of words and then demolishing them to start anew. As a whirlwind exposure to the philosophical tradition on transition from not-being to being, it is fascinating.

And Mulisch said: Let there be Lilith. For therein lies the true dilemma he wishes to discuss. The first failure in Biblical creation is representative of all the mistakes made by humans on the way to creation. They ignore loved ones in their single-mindedness, they create enemies for themselves in their hubris, and they destroy unintentionally. Creation is recognized almost as much by the difficulty along the way as by the final result. Mulisch suggests that “blood, shit, screams, and pain” were left out of the Biblical account.

And on the seventh day, as Mulisch would no doubt tell us, we can begin all over again.