In one of his most famous allegories, Plato writes in his Republic: “Imagine human beings living in an underground, cavelike dwelling… They’ve been there since childhood, fixed in the same place, with their neck and legs fettered, able to see only in front of them…” The prisoners’ view of the world is restricted to the shadows of figures projected on the wall before them. Knowing nothing else, they take these figures as real, and thus “in every way believe that the truth is nothing other than the shadows of those artifacts.”

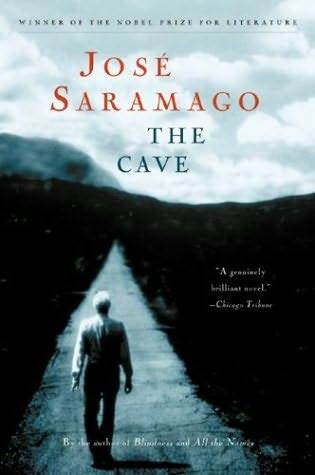

In his newest novel, The Cave, Nobel laureate Jose Saramago draws upon Plato’s image to make a cynical commentary on modern society. Unhindered by periods, paragraphs or quotation marks, Saramago’s prose consists of wry observation and rapid-fire dialogue that more closely resembles a stream of consciousness than a typical novel. Out of this surrealist haze emerges a bleak city rife with factories and consumerism.

Like many of Saramago’s settings, the city remains nameless, made universal by its teeming shantytown, smoke-clogged industrial belt, and dangerous central highway. At its heart, an ominous residential shopping complex called the Center grows larger by the day. Inside, fifty floors of shops, eateries, and gimmicky amusements like a rain-and-snow simulator and an artificial beach (with no sand) offer a self-contained world to which everyone covets admission.

Among the city’s lone holdouts are an old potter, Cipriano Algor, his daughter, and son-in-law, who live beside an idyllic mulberry tree in a village on the city’s outskirts. The son-in-law, Marcal, is a security guard at the Center. Cipriano delivers his ceramic pottery to its subterranean Buying Department on weekly trips in his rickety old van. On the day the tale of The Cave begins, the potter is informed that plastic crockery – “so good that it looks like the real thing”—has made his craft obsolete. His exclusive selling contract with the Center is retracted.

Faced with the threat of economic impotence, Cipriano and his daughter Marta decide to begin making hand-painted clay dolls instead. They hope that their efforts at constructing colorful representations of extinct cultures and professions (an Eskimo; a jester) will win over the Center’s callous buying department and allow them to continue operating the pottery. In the meantime, a stray dog adopts the family and the potter begins a shy romance with a local widow. Just when the doll project begins to seem fruitless, Marcal is promoted to resident guard, so the family has only ten days to move into a furnished apartment on the 34th floor of the Center. It is a chance many only dream of, but Cipriano dreads the forfeiture of his independence.

Saramago sees the Cave as representative of industrialized, capitalist societies the world over. It is not surprising that the 80-year old author has been an unyielding Communist for over half a century. In the 1970s he was jailed for supporting Portugal’s anti-Salazar revolutionaries, and he was in attendance—along with Gabriel García Marquez—three years ago at the Havana festivities marking the 40th anniversary of the Cuban revolution. Fidel Castro’s speech at the time, in which he said free market capitalism has “turned the planet into a giant casino,” may have provided inspiration for the Center portrayed in The Cave.

Saramago is beyond pessimistic. In December, he told the London Daily Telegraph, “The world today behaves like a madhouse. The worst of it is that the values we had more or less defined, taught, learned, are thought of as archaic as well as ridiculous… The human being should be the absolute priority. And it isn’t. It’s becoming less and less so.”

Among the signs of this decline, Saramago contends, are Israeli militarism and seemingly all institutionalized religions. Last spring the author drew heavy criticism for comparing the Israeli occupation of Palestine to Auschwitz. His 1991 book The Gospel According to Jesus Christ vividly describes God and the Devil both courting Jesus as a young man, despite the fact that God foresees the scourge of death and destruction that will soon be carried out in the name of Christianity. “One has to be God to countenance so much blood,” remarks the Devil.

Suffice it to say, the Vatican was less than pleased. The controversy that resulted in staunchly Catholic Portugal led Saramago and his second wife, to whom The Cave is dedicated, to relocate to their present home in the Canary Islands.

As usual, Saramago makes little effort to disguise his use of social metaphor in The Cave. His stories are seductively woven, even while they venture into ever greater extremes: at first marked by commonplace tokens of commercialism, the Center and surrounding city take on an increasingly eerie dimension. Ultimately, the world we recognized at first as a gray version of our own has been perverted into a terrifying case study of mankind’s tendency towards self-destruction.

The evolution begins believably enough. The Center’s buying department shows no compunction about casting off a supplier whose wares have ceased to sell. Its customers would rather use unbreakable, inexpensive dishes made of plastic rather than clay. After all, Cipriano reflects, “earthenware is like people, it needs to be well treated.” Ever practical, the city has ceased even to grow its food outdoors; its Green Belt furnishes the same fruits year round from within squat, ugly greenhouses. People throughout the city increasingly shop only at the gargantuan Center, certain to find everything that they need somewhere in its commercial catalogue, which has fifty volumes of fifteen hundred pages.

By the end of the novel there is no doubt: “Any road you take leads to the Center.”

The citizens’ need for constancy and convenience has come to dominate their lives, to the exclusion of natural beauty, culture, and even spirituality. Indeed, when Cipriano remarks that the head of the Buying Department seems to be analogizing the Center to God, the suspiciously talkative bureaucrat agrees: “Nowadays it comes to pretty much the same thing, I would not be exaggerating if I were to say that the Center, as the perfect distributor of material and spiritual goods, has, out of sheer necessity, generated from and within itself something that almost partakes of the divine.” Pressed by the inquisitive potter, the department head adds that, because of the Center, “life has taken on new meaning for millions and millions of people who before were unhappy, frustrated and helpless…”

The only vestige of emotion to withstand the torrent of commercialization, in Saramago’s grim estimation, is human affection. Order, love, trust, and loyalty are all that enable Cipriano’s family to resist the Center’s dehumanization. Cipriano and his family struggle constantly with the ramifications of their love, seeking to understand one another with a simplicity that is as heartfelt as it is painful.

As the clan faces the disbandment of the pottery and their inevitable move to the Center, no one is spared their share of frustration and tears. Yet, as Marta and Marcal remark, “People are so complicated, that’s true, but if we were simple we wouldn’t be people.”

Despite Saramago’s reverence for human emotion, handcrafts, and the mulberry tree, he offers few respites for the disheartenment that his metaphorical city engenders. (The mulberry tree is likely a reflection of the fig tree that Saramago recalled in his Nobel acceptance speech, under which the author used to listen to his grandfather tell stories.) The author’s own brand of Communism, for one, appears an unlikely cure in 2003.

Still, when underground digging at the Center uncovers a real cave, containing the skeletons of six people who sit tethered just as Plato described, the Algor family takes the revelation to heart. But there is no returning to their earlier lives: the pottery is defunct and, what’s more, the dominion of the Center pushes steadily outward.

Saramago’s chilling description of a cruel, artificial world resonates so thoroughly that when the family finally decides to pack their belongings into the old van and escape to greener pastures, we would like to know how to join them. The author offers few clues to their final destination.

Fortunately, Plato did not share Saramago’s sparse style. Harkening back to his theory of forms, Plato equates the light that greets a prisoner lucky enough to escape the cave with the most powerful form of all—the good. “In the knowable realm, the form of the good is the last thing to be seen, and it is reached only with difficulty. Once one has seen it, however, one must conclude that it is the cause of all that is correct and beautiful in anything, that it produces both light and its source in the visible realm, and that in the intelligible realm it controls and provides truth and understanding, so that anyone who is to act sensibly in private or public must see it.”

That, at least, ought to be inspiration enough to keep up the search.