At sixty-one years of age, the South African novelist J.M. Coetzee has crafted several treasures of contemporary fiction, including his most recent novel, Disgrace. The only author ever to win two Booker Prizes, he enjoys the great respect of contemporary novelists and critics. To the delight of his literary colleagues and fans, he has selected this point in his formidable career to consider and comment on the works and reputations of many great writers who came before him.

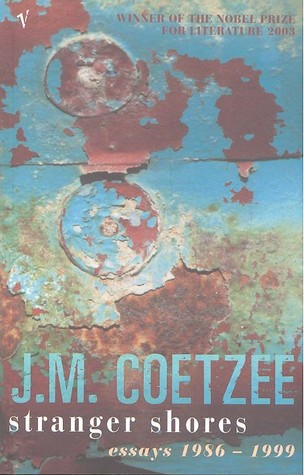

In Stranger Shores: Literary Essays 1986-1999, Coetzee discusses the canonical giants of several continents. The great novelist and critic boldly set out for distant shores; one of his most remarkable triumphs is to describe in thorough detail the literary traditions of countries vastly different from South Africa. His unique background allows him to comment on these traditions with lively and original insight. Few contemporary writers could produce such compelling commentaries on Samuel Richardson’s novel of 1798, Clarissa, or on Daniel Defoe, whose Robinson Crusoe inspired Coetzee’s own novel, Foe.

In addition to his chapters on Richardson and Defoe, Coetzee brilliantly criticizes several major writers whom you may have always wanted to read but still neglected. The collection covers not only eighteenth and nineteenth century giants (Defoe, Richardson, Turgenev), but also masters of twentieth century European literature (Byatt, Mulisch, Rilke) and dominant figures of Latin American, African, and even Caribbean letters (Borges, Lessing, Phillips).

In a typically far-reaching article, “What is a Classic?” Coetzee manages insightfully to link J.S. Bach, T.S. Eliot, and the Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert. This essay opens the collection and articulates Coetzee’s overarching task. The novelist-turned-critic has set out to exercise “one of the instruments of the cunning of history,” to affirm the privileged status of several classics by slowly and meticulously picking them apart. In doing so, Coetzee inserts himself into the European, African, and colonial literary traditions. His description of Clarissa’s body, for example, complements and even bests many older, stuffier Richardson commentaries.

The book’s opening reflection on the classics also highlights one of Coetzee’s most consistently charming techniques: his revealing treatment of great writers as literary characters. In the case of “What Is a Classic?” the protagonist is T.S. Eliot, whom Coetzee alternately describes as “a man with the magical enterprise of redefining the world around himself” and “a man whose narrowly academic, Eurocentric education has prepared him for little else but life as a mandarin in one of the New England ivory towers.”

This complex portrait of a dreamer who overestimates his role in history resembles many of Coetzee’s later literary profiles. His entertaining sketches of neurotic, almost insanely passionate writers recall Cynthia Ozick’s observation that, “If we had to say what writing is, we would have to define it essentially as an act of courage.” Take, for example, Coetzee’s profile of the twentieth- century novelist Harry Mulisch, who writes in depth about his harrowing, obsessive work habits. Unhappy with a rough draft, Mulisch records a sense of “intellectual despair” and “powerlessness mingled with dreadful loathing…at the thought of having to go back to (the manuscript).” He later concludes desperately, “I am a total stranger to myself and could be either a critic or a commentator of my own work.” One might like to urge Mulisch to get out of the house, or at least to find a hobby.

Despite this emphasis on writers’ obsessions, Coetzee treats each author with a remarkable amount of respect, sympathy, and patience. He writes always with a sharp eye for detail and a sense of critical restraint. For example, in his essay on Borges, Coetzee quotes Harold Bloom: “What Borges lacks, despite the illusive cunning of his labyrinths, is precisely the extravagance of the romancer…[He] has never been reckless enough to lose himself in a story, to our loss, if not to his.” Coetzee proceeds modestly to describe Borgesian stories in which the author most certainly “loses himself” in his “laconic, haunting, and sometimes brutal” work. Bloom’s assertion seems to pale in comparison to Coetzee’s precise, well documented, and meticulous insights. Faced with Coetzee’s delicate criticism, the reader is actually persuaded that Yale’s most famous literary critic should want to follow Coetzee’s example and avoid such sweeping conclusions.

True, Coetzee’s patient and extremely serious tone becomes a bit aggravating at times. One would occasionally like the author to use just a little humor when discussing his literary contemporaries. For example, he could poke quite a bit of fun at the melodramatic Dutch novelist and travel writer Cees Nooteboom, who produces this spectacularly awful sentence: “Truth, reality, lies, illusion, the thing itself or its name, are all will-o’-the-wisps seeking to relegate the confusing tangos of meaning to the ballroom of postmodernism or of metafiction, just to be rid of them for a while, like a hornet that you chase away either because you are afraid or because you find it annoying.” Coetzee’s restrained commentary on Nooteboom is admirable, but much kinder than it needs to be. In fact, in his less persuasive moments, Coetzee does overburden his own prose, producing such confusing sentences as this: “Max Delius’s Pythagoreanism belongs to a neo-Platonic cosmology that Harry Mulisch himself has been propagandizing, under the name ‘octavity,’ since the 1970s.” This clutter of jargon, however, is an exception to Coetzee’s generally clear and graceful language.

But if the prose becomes a bit dry at some points, it is still intelligent and original. Coetzee’s close relationship to his literary ancestors allows him to revive and freshly reinterpret some of the greatest works in the canon. One need only turn to the concluding paragraphs of his review of Nobel Prize winning author Naguib Mahfouz to appreciate the critic’s shrewd and careful style. Listing various mistranslations of one of Mahfouz’s tales set in pre-modern Cairo, Coetzee makes the typically sharp-eyed observation that “‘Call girl’ surely depends on the existence of telephones.” From these minute stylistic infelicities to broader analytical insights, Coetzee continues to provide new interpretations and insights to those of us with lesser vision.