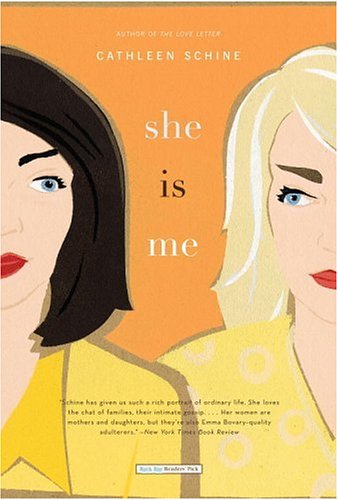

Cathleen Schine’s latest novel, She is Me, borrows its title from arguably the most celebrated statement on inspiration. When asked about his model for Madame Bovary, Gustav Flaubert famously said, “Madame Bovary, c’est moi.” Alas, try as Schine might to re-write Flaubert’s master work of marriage and adultery, boredom and excitement, tragedy and parody, She is Me is no Madame Bovary.

Schine’s novel certainly has its merits. She is Me cleverly distributes Emma Bovary’s most notable character traits onto three characters, three generations of women from the same family. First, representing Emma’s vanity, there’s Lotte, an Emma for the octogenarian who obsesses over fashion despite her losing battle with a disfiguring skin cancer. Then there’s Greta, Lotte’s daughter, who enacts Emma’s lust for extramarital excitement motivated by ennui. Finally, there’s Greta’s daughter, Elizabeth, who’s adapting her academic article entitled “The Way Madame Bovary Lives Now: Tragedy, Farce, and Cliché in the Age of Ikea” into a screenplay. As Emma Bovary structures her life around fictional ideals, Elizabeth is a chronic movie watcher who, deluded by fiction, makes an attempt at adultery. Elizabeth represents Emma as the over-enthusiastic reader.

Unfortunately, Schine’s innovative decision to parse Emma’s traits between three characters results in three underdeveloped heroines. Rather than three Emmas, the reader finds three parts of Emma that never quite add up to the whole. Emma Bovary is a profoundly ambiguous character: likable in her desire for excitement and darkly destructive in her egotism. In contrast, Schine sugarcoats her characters: Lotte, Greta and Elizabeth remain consistently friendly and likable, never dark or destructive.

What, exactly, is the reader supposed to think of Lotte, who comes to Thanksgiving dinner disfigured due to a recent operation yet hopes that everyone will only notice her new jacket? Flaubert gives Emma a lust for Parisian life in the form of an obsession with fashion in order to show her petty, superficial consumerism. Schine turns consumerism into heroism: in order to keep her partial Emma “nice,” she asks the reader to understand Lotte’s vanity despite cancer as an admirable display of perseverance in the face of hardship. The narrator writes, “Lotte’s face was white on one side and russet on the other. Her mouth was twisted now, too, and a growth the size of a small grapefruit protruded from her jaw. But it was her, it was Mother with her smooth, stylishly cut white hair, her new jacket, the one she’d ordered from Victoria’s Secret, her chic pants that hung a little on her now that she’s lost so much weight.” Seeing her mother in this state, Greta exclaims, “Mama! What a fabulous coat!” Lotte wears a “fabulous coat” to compensate for her growth “the size of a small grapefruit” and the reader is supposed to think, “what a fabulously strong woman.” However, this scene borders on the ridiculous rather than the darkly humorous, the melodramatic rather than the tragic. Lotte’s little way of persevering is pitiful, but not compelling.

One could argue that the feeling of pity rather than enthusiastic encouragement is just what Schine’s after: she’s trying to make the reader find consumerism pathetic. But if that is the reaction that Schine is attempting to produce, then she should have employed a more distanced third person narrator. Schine never records an opinion that does not belong to one of her characters. Since all of Schine’s characters think Lotte is “fabulous,” if somewhat perplexing in her continued attachment to Victoria’s Secret, then the reader has no true guide to make him or her judge differently. There is no narrator to make the reader realize that condemnation is being solicited rather than encouragement.

Greta, at first, seems a more promising character. Sick with cancer like her mother, Greta wakes up one morning to realize that cancer is not the only thing she’s sick with – she’s sick with boredom, and sick of her husband. Schine does a good job making Greta’s ennui approach Emma’s. The narrator records Greta’s thoughts in indirect discourse, “Tony would rumble out of bed soon wondering what was for breakfast. Greta never understood why he had to ask this question each and every morning since he made his own breakfast and it was always toast with low-fat cottage cheese.” In order to convey that Charles Bovary, Emma’s husband, is boring and bourgeois, Flaubert describes him enjoying simple meals, at the same time every day. Similarly, Tony’s predictable choice of low-fat cottage cheese aligns him with the boring middle-class obsessions of the modern day: health and diet. Tony, like Charles, is too predictable. Schine begins to go wrong with Greta in the descriptions of her adultery. Emma cheats on Charles with Rodolf, an exciting aristocratic adventurer, the very opposite of her husband. Greta, too, pursues newness: her beloved is a young movie director rather than an average doctor, a woman rather than a man. However, in her new relationship Greta merely seeks companionship, not adventure. Flaubert’s narrator explains that Emma finds disappointment in her affairs because she “rediscovers in adultery the platitudes of marriage.” Greta, too, finds platitudes: a lover’s quarrel, sameness, and reliability. Unlike Emma, she doesn’t mind at all. As Schine tones down Greta’s vanity by coding it as admirable perseverance, she limits Greta’s potentially harmful urge for excitement.

Elizabeth’s character is by far the best developed. Yet, her adventures always seem to verge on farce rather than true drama. Elizabeth fancies herself a modern gal: she refuses to marry her longtime boyfriend, Brett, because if you’re not married, you can’t technically be accused of adultery. Elizabeth’s first extra-relational love object is Larry Volfmann, her producer. Volfmann invites her out for drinks and Elizabeth immediately assumes that he is consumed by passion. At a bar by the beach, Volfmann leans over close to Elizabeth and says, “You’re the only one who, the only one who would understand . . .” After a pause Volfmann completes his thought: Elizabeth is the only one who would understand “Joseph Roth.” The time lapse of the ellipsis is enough for Elizabeth to think Volfmann is confessing some deep emotional connection when he is in fact hoping for intellectual companionship. By having Elizabeth mistake friendship for romance, she turns a potentially dangerous craving for satisfaction into a merely embarrassing, ultimately mundane confusion. Emma’s exciting and intentional recklessness becomes Elizabeth’s unintentional thoughtlessness.

When Elizabeth finally succeeds in finding excitement outside of marriage, Schine describes her encounter like a cross between an awkward high school fling in the tradition of Fast Times at Ridgemont High and a bad soap opera: “The moon shone on the water, a long wavering cord. The waves collided onto the sand. And, cheerless still, but overcome with desire, Elizabeth turned and kissed Tim on the mouth . . . Holding her hand, he led her back to the car. In the front seat, Temple [the dog] growled irritably, like a bad conscience, and Elizabeth knew what she was doing was pointless.” From the clichéd beach to the grungy back of a car, Elizabeth’s adventure is a far cry from Emma’s passion. In a cross between the melodramatic and the banal, Brett watches a lover’s quarrel between Elizabeth and Tim and realizes what’s been happening. The narrator writes that, “Brett had been emptying ice into an ice bucket. He stared back at her, still holding the bag as ice cubes fell into the silver bucket, overflowing, littering the counter.” It is emblematic of Schine’s work that Brett expresses his anger and surprising by causing an ice bucket to overflow rather than, say, breaking the ice bucket.

Elizabeth’s high-school affair does not last long: she quickly backs down and comes to the realistic, yet run-of-the-mill realization that marriage and fidelity are better alternatives to adultery. Schine’s Elizabeth would have been a far more compelling character if she were less likable—if, like Emma Bovary, she never realized that other people matter. Similarly, Greta would have been more complex if, like Emma, after leaving Tony, she found dissatisfaction, and expressed dissatisfaction with her new fling. And, Lotte would have been more intriguing if her penchant for fashion despite cancer were not only an attempt at describing heroic perseverance, but, as in Madame Bovary, a dark commentary on vanity despite more profound matters. Unfortunately, Schine never dares to make her characters unlikable. Why? She is Me is not Madame Bovary. She is Me is rather “The Way Madame Bovary Lives Now: Tragedy, Farce, and Cliché in the Age of Ikea.” Schine has made a valiant attempt at converting Flaubert’s famous novel into a modern context just as Elizabeth tries to turn her academic article into a screenplay. Schine has attempted to write Madame Bovary light. Unfortunately, just as Elizabeth can never quite convert Flaubert’s novel into a good screenplay, Schine loses too much in translation. By making Flaubert’s Emma into three friendlier characters, Schine flattens complexity into one-dimensionality.