By December 29, 1999, Abdel Wahab al-Effendi had been convinced of Islamism’s failure. Why should you care? He is a senior writer for al-Quds al-Arabi (Arab Jerusalem), a major Arabic-language newspaper based in London, in which al-Effendi’s article entitled, “The Sudanese Experiment and the Crisis of the Contemporary Islamist Movement,” ran on that day. The Sudan’s principal Islamist, Hassan al-Turabi, had been ousted earlier that month, and al-Effendi sought to explain why. After all, the Sudan had become a political disaster without any Western nation’s interference. There were only the Islamists to blame.

Americans wish they could share al-Effendi’s dismal outlook on a political movement as new to their cultural landscape as the war it started, on September 11, 2001. Their conclusion is simple: Muslims, who have a problem with Western cultural values, succeeded in destroying downtown Manhattan. What could that be, except a sign of strength?

Demolishing buildings is fine, if you are Godzilla. Abstract political movements, however, have a distinctly different agenda from our favorite giant lizard. Usually, they aim to feed and clothe people, and maybe, after several years, turn themselves into a legitimate government. Indeed, these aspirations were central to the development of Political Islam, or Islamism, since its birth in the early 20th century. Specifically, Islamism sought to use religion as a way of coping with the process of decolonization: it offered unity, stability, even a system of finance to populations that wouldn’t have had them otherwise. In the 1960s, the heyday of Islamism, intellectuals all over the world even saw it as a progressive force, one that could foster fundamental human rights in populations that had never before experienced them. As the story went, Islamism could succeed where Western imperialist institutions had failed, because all its tenets were fundamentally rooted in Near-Eastern societies. The theoretical architects of Islamism claimed they were looking no further than the Quran for their ideas, and everyone believed them. Now, it all seems preposterous.

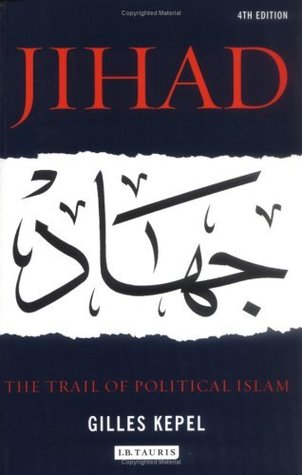

Dr. Kepel, a political scientist from the Institut d’Études Politiques (IEP) in Paris, has outlined the theoretical basis of Islamism and traced the history of its failure. The book is a masterpiece of scholarship, and furnishes separate analysis for every geographic region where Islamism is important today. The original title, which the hopelessly inept English translator chose to discard, is Jihad: the Expansion and Decline of Islamism. The book is divided into two sections of equal length, aptly entitled Expansion and Decline. Clearly, the author is trying to drive home a point here: Islamism, as we know it today, will never have a resurgence. The experiment is over. While Mr. Kepel is very careful never to imply that this occurrence was inevitable, he seems to believe the theoretical disunity of Islamism played an important part in determining its fate. Islamism came to the fore at a time of crisis for Arab national politics. To secure their place in desperate times, theorists of Islamism promised everything to everyone—security to the rich, revolution to the poor, free speech to intellectuals, moral order to conservatives—in the hope that their powerful religious message would keep obvious contradictions from popping up. In retrospect, it is amazing the façade held up as long as it did.

Kepel identifies two seminal theorists of Islamism: Mawlana Mawdudi, a Pakistani religious scholar and inspiration for the Deobandi School and the Taliban, and Sayyid Qutb, founder of the Muslim Brothers in Egypt. These men took a lot of inspiration from European fascism and Soviet-style Communism in setting up the fundamental tenets of Islamism. Mawdudi, writing in Urdu and following the logic of 19th century South Asian Muslim thinkers, came up with the notion of the Muslim State. Qutb popularized this idea in the Arab world, while advocating the Sharia, the supposed Muslim ethical doctrine contained in the Quran, as an instrument for social justice.

Kepel tells us that the fundamental fissure in the Islamist movement takes place on class lines. Islamist revolutions, most notably in Algeria and Iran, often followed the patterns of European revolutions for social justice, ending with a moderate bourgeois element co-opting, and then suppressing, what had begun as a radical movement of the poor. Islamism depends on keeping both rich and poor in its camp.

Islamists can only hold power where they maintain political and economic support of the rich, along with the social mandate of the poor. Intellectuals and the conservative merchant class are the links necessary to hold such an alliance together. The only Islamist movement to successfully court all these disparate groups was in Iran, under the leadership of the master rhetorician of Islamist theory, Ayatollah Khomeini. It resulted in the 1979 Islamic Revolution and the introduction of Vilayat-e Faqih, or clerical government. Khomeini ruled until his death ten years later, but only by employing a crippling 10-year war, thousands of hackneyed speeches to the poor, and a fatwa on poor Mr. Rushdie as distractions. This pathetic display is the closest Islamists can claim to have to come to victory. Many Sunni Muslims, al-Effendi included, feel they cannot even claim this much, since Khomeini was a Shi’ite.

What, then, of Sept. 11th, Islamism’s grand victory? It is actually a dramatic death knell, a symbol of how desperate Islamists have become. After the Gulf War, any Islamist hopes of a unity amongst rich and poor were as good as forgotten. U.S. intervention, on behalf of the conservative Saudis, forced all political hands and divided the Islamist camp. Now, all of those whom Islamism has failed have no power structure demanding loyalty. Kepel repeatedly notes the demographic importance of the first generation who grew up never having known colonialist rule, and how their expectations are changing the system. There is a possibility, believes Kepel, for the entire Islamist process to transform itself, just as the passing of fascism initiated democracy all over Europe. People want free markets and human rights, and will not long support a system that doesn’t provide them.

So, the next time you crack open your copy of al-Quds al-Arabi, should you find an article echoing al-Effendi’s, please, don’t be surprised. As time goes on, the number of such articles will steadily catch up with the popularity of sentiments they express. In fact, one would expect the most ardent critics of Islamism to be those involved in it, since they have the largest stake in changing it: Islamism destroyed our World Trade Center, but it has destroyed their entire society. Already, in 1999, al-Effendi was engaging in some questionable historical “revisionism,” saying that the Muslim Brothers had originally touted free markets and democracy at their founding in 1930. Part lie, part rhetoric, it makes for a most welcome reinvention.