Though many jazz enthusiasts would agree that classic jazz belongs to the modern art tradition, until now no author had completed a comprehensive analysis of jazz through this lens. Alfred Appel Jr.’s learned book Jazz Modernism: From Ellington and Armstrong to Matisse and Joyce places classic jazz in the cultural and historical context of modernism. But, more importantly, the work accomplishes this task while celebrating the music of jazz and the artists who created it.

Appel’s book celebrates jazz’s greatness through serious scholarly analysis of the music and through the author’s own expressions of enthusiasm, but an audience unappreciative of jazz may ultimately not be converted: Jazz Modernism is dense reading. Then again, what description of music could be expected to rival the real thing? As one artist said, “Where words fail, music speaks.”

Still, when Appel describes Charlie Parker’s 1951 live performance in front of Igor Stravinsky at Birdland, Buddy Rich’s impromptu drum battle with Armstrong’s all-star Sid Catlett, or Louis Armstrong’s sweaty set at Stanford University, the author’s prose is as exciting as a Waller LP. It is in these passages where the sagacious Appel becomes just like any jazz fan, mesmerized by the musicians he writes about so vividly.

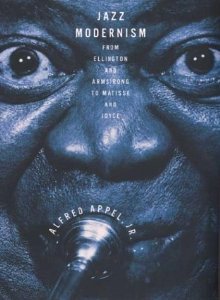

Appel argues that classic jazz holds up over time because it is deliberately accessible music. He identifies accessibility as the common element in the best works of art, and he practices it himself through references to baseball and hip-hop, and the inclusion of 127 stunning pictures. But Jazz Modernism is not for your coffee table. Rather, it is a dense, metaphorical explanation of the idea that jazz music developed alongside modern architecture, art, and literature. Formal prerequisites for reading Appel’s book are few; he conjures the countless works he draws from with some generalized description. Even if readers have not scrutinized a particular Jack Teagarden solo or waded through Ulysses, they will probably understand most of this book. Still, Appel’s readings of Armstrong trumpet solos or Calder wire sculptures are sometimes detailed and allusive to an extreme.

Appel discusses Louis Armstrong’s music in his aptly titled chapter “Pops Art,” the longest in the book. Here, the author argues that Armstrong subverts the often-racist messages of trite popular songs that romanticize the antebellum South. To jazz purists, the verbal content of Armstrong’s songs is less important than the melodies. But jazz neophytes can take comfort that Jazz Modernism is never more musically technical than in its brief discussion of the ubiquitous “I Got Rhythm” chord progression.

Appel shows that jazz is a multicultural effort while paying due homage to the dominant African-American roots of the music, reminding us that in one performance of “White Christmas,” Charlie Parker renamed the song “We Wish You a Merry Russian-Jewish Afro-Cuban All-American Christmas, Man” and evoked each of these traditions in his solo.

Of course, in a cultural discussion of jazz, any scholar must mention the unfortunate association of jazz masterpieces with “the most banal or uncertain carnival and vaudeville and nightclub acts” spawned from certain “putative Caucasian needs and expectations.” Appel includes troubling anecdotes to explain how this association forced jazz musicians to prove their dignity through their instruments. Even Ellington’s master drummer Jo Jones must have found this difficult when he “once had to cover up the flatulence of a talking horse with `the loudest drum roll in history.’” Appel goes on to assure white listeners that they may relax and enjoy Armstrong’s performance of the problematically titled song “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny” without accusations of Confederate nostalgia. In this case, the author illustrates how Armstrong’s subtle grammatical and vocal inflexions express the complexity of the end of slavery, as African-Americans were met with no “Promised Land in the industrialized North.” It is in this sort of incisive analysis where Appel’s style is most effective: “Armstrong the vocalist goes home by dropping an octave as he sings the word `shack,’ thereby adding a basement bunker—a safe place in case of a big storm or a Klan raid, central heating by homemaker Armstrong.”

The book features several illustrations, often without captions. The “Pops Art” chapter opens with a photo of a young Armstrong contemplating the potential of his horn and closes with Carlo Carrá’s 1914 verbal collage Free-Word Painting. This final image of “Pops Art” exemplifies Appel’s assertion in the first chapter that Jazz musicians, like the collage-minded cubists and pop artists, are rag pickers, synthesizing a coherent composition out of quirky and disparate elements.

Appel’s argument in “Pops Art” stretches over Armstrong’s whole career and draws parallels between Armstrong’s music and Walker Evans’s photography, Picasso’s sculpture, and Matisse’s collages. Miles Davis fans may wonder why he is mentioned parenthetically in Appel’s chapter on Armstrong but not included formally as one of Appel’s Jazz Modernists. Certainly Davis’s music remains as accessible as Armstrong’s through most of the 1960s, though Appel chooses to truncate his argument at 1950. Similarly, Ellington aficionados may be confused that his name is included in the subtitle, though the author devotes far more text to stride pianist Fats Waller.

Appel finds himself in the difficult position of distinguishing among the accessible, the easy, and the bad in contemporary art. He alludes to the disintegration of former lines between high and low art, but offers no satisfying criteria to distinguish today’s musical masterpieces from a beat-box drone. And artists must wonder, upon reading his book, how to balance accessibility to the public and honesty to their personal visions. Appel argues that Joyce rewards his readers with the most accessible chapter at the end of Ulysses for those who make it that far. Does this then excuse the confounding “Oxen of the Sun” chapter? If Coltrane had clipped his later solos to a more manageable length, might Appel have provided him a substantial space in Jazz Modernism? And why would a more contemporary jazz album like Miles Davis’s 1972 record “On the Corner” lack the enduring power of Davis’s earlier music despite his attempt to fuse a jazzy past with the more accessible funk trends of the times? Appel’s approach to classic jazz, upon extension to other art, generates these questions; the author does not concern himself with modern jazz and whether or not it qualifies as “Jazz Modernism.” Unfortunately, that is more of a paradox than a swinging pun.

But even if readers cannot quite apply Appel’s way of understanding classic jazz to explain contemporary art and music, they will close Jazz Modernism convinced not only of the artistic merits of classic jazz, but also of the need for the joys of jazz today.