The penis goes by many names: “dipstick,” “peenie-weenie,” “lovepump,” “wonder worm.” Jonathan Franzen culls these synonyms from a list of no fewer than 45 in Dr. Susan Block’s 10 Commandments of Pleasure. Surveying a wide range of pop-sex books, he learns the etymology of “cunnilingus” and the importance of strengthening the pubococcygeal muscles. Yet, as he notes in his essay “Books in Bed,” these instructional tidbits irritate him. He yearns for America’s yesteryear of repression, when kids searched for dirty words in Webster’s Collegiate, and coitus was an exciting taboo. The current glut of clinical guidebooks denies couples the thrill of discovering sex privately. Franzen mourns their lost right to be alone.

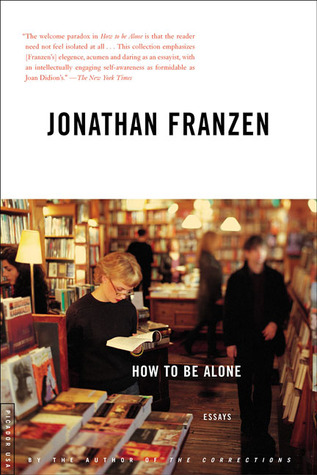

For more on this eloquent advocate of sexual discretion, don’t ask Oprah. Last year, Franzen questioned his own decision to appear on TV with Ms. Winfrey, who responded disinviting him. The Corrections nevertheless sold like Bridget Jones throughout America and won the 2001 National Book Award. Franzen, whose two previous, critically acclaimed novels had been largely ignored, took a break from fiction in order to publish How to Be Alone. This book is a collection of fourteen brilliant responses to a culture that turns to guidebooks for erotic synonyms of “peenie-weenie.”

Franzen’s principal enemies throughout How to Be Alone are television, cyberland, therapeutic literature, caller ID, advertising, the over-prescription of anti-depressant drugs: anything that promises comfort at the cost of meaningful human experience. His blanket term for these products is “technological consumerism.” In order to illustrate its restrictive influence, he describes the seemingly disparate lives of a Southern Baptist Georgian and a black lesbian New Yorker:

Both the New Yorker and the Georgian watch Letterman every night, both are struggling to find health insurance, both have jobs that are threatened by the migration of employment overseas, both go to discount super-stores to purchase Pocahontas tie-in products for their children, both are being pummeled into cynicism by commercial advertising, both play Lotto, both dream of fifteen minutes of fame, and both have a guilty crush on Uma Thurman.

According to Franzen, techno-consumerism is threatening the private dignity of the American citizen. In one example, neither the New Yorker nor the Georgian can easily maintain the illusion of a unique sex life when Susan Bakos, author of Sexational Secrets, is advising all of America to practice thirteen illustrated masturbatory techniques.

Though not all of Franzen’s essays are as funny or titillating as his survey of pop-sex literature, the most memorable tend to repeat the format of “Books in Bed” by uncovering some way in which techno-consumerism is damaging private dignity. “Imperial Bedroom,” Franzen’s response to the Lewinsky scandal, focuses on the erosion of civic life. Reading the Starr Report, Franzen can’t understand why he feels as if his own privacy—not Clinton’s—is being violated. His epiphany: the American citizen – with his palatial SUV, tinted windows, caller ID, and in-home entertainment system—enjoys plenty of privacy, but it’s undignified and senseless when it can’t be defined against a rich public life. “The need to put on a public face is as basic as the need for the privacy in which to take it off,” he writes. By setting his sex narrative in one of the last bastions of civic life, Starr has permanently disfigured America’s public face. If Franzen sounds to you like he’s clinically depressed, you aren’t entirely wrong. In his most moving piece, an essay that appeared in Harper’s in 1996, he describes his struggle with depression, and his ultimate acceptance of tragic realism: a negative, but bearable, way of viewing the world. His subplot is nothing less than the status of contemporary fiction; the victim, America’s writers; the villain, each techno-consumer who prefers TV and Prozac to novels and a good, long look at his perverse way of life.

After his divorce and the commercial failure of his second novel, Franzen began to retreat from the world. Horrified to read of America’s involvement in the Gulf War—its “dreaming of glory in the massacre of faceless Iraqis, dreaming of infinite oil for hour-long commutes, dreaming of exemption from the rules of history”—Franzen doubted his ability to entertain a mass audience with which he seemed to share no common moral ground. Since college, his literary role model had been Catch-22, with its enormous readership and subversive assault on American culture. But the middle-aged Franzen wasn’t living in Joseph Heller’s heyday. The fast-paced world of television, movies, and print journalism had already supplanted the social novel as a means of reportage and cultural critique. “Panic grows in the gap between the increasing length of the project and the shrinking time increments of cultural change,” Franzen writes. “How to design a craft that can float on history for as long as it takes to build it?”

Flannery O’Connor’s response to the decline of the social novel was to argue that the best fiction is always regional. Authors should not worry about packing in every detail of contemporary American life, but should instead strive “to embody mystery through manners”: to examine the seemingly mundane ways in which members of one community confront or neglect the meaning of existence. The formula worked easily for O’Connor, but not for Franzen. A large portion of his desired readership no longer cared to examine its manners or its mysteries, since the trappings of techno-consumerism eliminated the need for many unpleasant human interactions and distracted buyers from their existential angst.

Hence the title of Franzen’s essay, “Why Bother?” Why attempt to write serious fiction when so many Americans couldn’t care less? Franzen turned to Don DeLillo, who urged him not to write for a sizeable market, but for personal freedom. Writing, according to DeLillo, “frees us from the mass identity we see in the making all around us. In the end, writers will write not to be outlaw heroes of some underculture but mainly to save themselves, to survive as individuals.” Franzen revived his third novel, The Corrections, with a jolt of tragic realism: an unyielding attention to all of the “human difficulty beneath the technological ease, to the sorrow behind the pop-cultural narcosis.” He wrote for himself; he wrote for his characters. And, in a bizarre twist of fate, countless techno-consumers read his novel.

They should read his essays, too. Energy and precision distinguish each of these pieces, from the eerie history of the supermax prison in Fremont County, Colorado, to the rueful memories of the Oprah saga. You’ll cringe when a cameraman instructs Franzen to drive across the Mississippi River and look contemplative. You’ll reach for the Kleenex when he sifts through some papers on which his father, fighting Alzheimer’s, scribbled the names and erroneous birth-dates of his children. And you will undoubtedly note the maturity of the later essays: the “movement away from an angry and frightened isolation toward an acceptance—even a celebration—of being a reader and a writer.” Franzen may not rejoice when he contemplates the new millennium, but he will nevertheless inspire you. His prose is smart, powerful, and always improving—and that’s reason enough for sticking around.