It is no surprise then that Rushdie’s intellectual inquiries have so often centered around the notions of borders and boundaries; transgressions and journeys; the crossing of frontiers, and the struggle to come to grips with that often elusive idea: home.

Rushdie was just a few weeks old when the violent Partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 sliced his family into two geographical parts “as a taut wire cuts through cheese.” Those events would inspire his breakthrough 1981 novel, Midnight’s Children, which questioned the boundaries that separate one country from another, this language from that, story from storyteller, and the world of reality from that of the human imagination. Thirteen years after Partition, Rushdie would move with his father to London, the city into which the expatriates Gibreel Farishta and Saladin Chamcha would plunge from out of the sky in the opening pages of The Satanic Verses (1988).

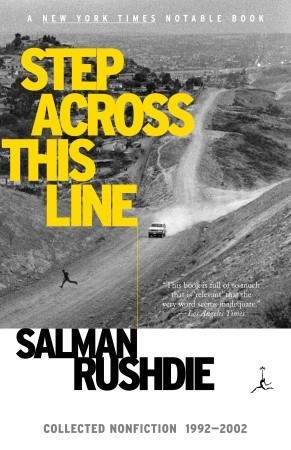

Issues of boundaries and transgression are once again central in Step Across This Line, a resplendent new collection of a decade’s worth of Rushdie’s essays, columns, speeches, and letters. The book takes its title from Rushdie’s talks for Yale’s Tanner Lectures on Human Values, delivered in February of 2002. The imperative title is an entreaty to the reader: “Free societies are societies in motion,” Rushdie writes, “and with motion comes friction. Free people strike sparks, and those sparks are the best evidence of freedom’s existence.” Free people cross boundaries; they step across lines.

Sadly, that is not always as easy as it ought to be. The “exile” sentence above first appeared in The Satanic Verses (its sentiment is revisited in Step Across This Line), “a legitimate work of the free imagination” for which Iran’s late Ayatollah Khomeini—without ever having read a page of the book—issued the infamous international bounty on Rushdie’s head. The bounty would not be lifted until 1998. (Rushdie was not permitted to set foot back in India, which banned Verses even before its public release in that country, until 2000.)

Today, Rushdie is undoubtedly among the world’s greatest living writers of prose; and perhaps the most remarkable part of such a statement is that the man is still living at all. After all, we see in Step Across This Line how throughout the period of the fatwa, Rushdie’s untenable situation was often approached (by high-ranking government officials worldwide, no less) as one would approach a dental cavity: you want it to go away enough that you’re willing to allow for a very unpleasant procedure to take care of it. The British government, while begrudgingly providing Rushdie with protection, routinely refused him meetings, attempted to stifle his voice, and treated him like a man who ought to lie in the bed that he—not a murderous foreign dictator—had made for himself. The nation’s tabloids screamed headlines like “Rushdie Inflames Muslim Anger Again” (for requesting that Verses be published in paperback), while Rushdie himself was left to ponder England’s reluctance to uphold freedom of expression, as well as “the right of its citizens not to be murdered by thugs in the pay of a foreign power.” In one darkly comic instance, Rushdie was told during a visit to Copenhagen that Danish officials were avoiding him because they did not wish to endanger relations with Iran, to which they exported great quantities of feta cheese.

We learn all of this in the section of the book entitled “Messages from the Plague Years,” which samples Rushdie’s writings through the decade of the fatwa. These are the writings of a man trapped in a room (or a succession of rooms at undisclosed locations), within a country that every day becomes less hospitable and further from feeling like home. In April 1993, after the publication of a Times of London op-ed suggesting “that fully two-thirds of Tory MP’s [Members of Parliament] would be delighted if Iranian assassins succeeded in killing [Rushdie],” a desperately frustrated Rushdie wrote: “Either we are serious about defending freedom, or we are not. … If these MP’s truly represent the nation—if we are so shruggingly unconcerned about our liberties—then so be it: lift the protection, disclose my whereabouts, and let the bullets come. One way or the other. Let’s make up our minds.” He notes the difference between borders designed to keep people in (e.g., the Soviet Union), and those designed to keep others out (e.g., parts of the United States). During the Plague Years, Rushdie felt the sting of both.

The book’s final section contains its only new material, which may not even be all that new to many of us: it is the text of his two speeches delivered last year at Yale. But the material, with few exceptions, is worth a second and a third read; these speeches, like so many of the essays, are timeless.

“The Grail is a chimera,” Rushdie said last February to a packed Battell Chapel. “The quest for the Grail is the Grail.” Rushdie and his work may never fully emerge from the Plague Years, or even from the personal and national trauma of partition; and the man himself may always feel like an outsider wherever he goes. But his work continues to question boundaries, and to dismiss the limits that others define on what can and cannot be said. It has long created friction, and it continues to make brilliant sparks.